By Charles Harry Nthewa, Keston Njira, Patson Nalivata, Joseph Chimungu, and Austin Tenthani Phiri

Soil nitrogen depletion remains a critical barrier to sustainable crop production in Malawi’s drought-prone smallholder farming systems. This study investigated the influence of cowpea–pigeon pea intercropping and residue management on soil nitrogen dynamics. Results show strengthened nitrogen cycling through biological nitrogen fixation, improved residue quality, and increased residue biomass. This integrated approach provides a climate-smart pathway to restore soil fertility and enhance the resilience and productivity of smallholder farming systems in Malawi’s drought-affected regions.

Sustainable intensification of agriculture is increasingly critical in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA), where soil degradation, declining productivity, and climate variability threaten food security and farmer livelihoods (Ahmed et al., 2022). In Malawi, soil fertility decline is primarily driven by continuous monocropping, residue burning, erosion, and the diversion of crop residues for livestock feed, leading to severe nutrient depletion (Mwale et al., 2011; Ngwira et al., 2012a; Raj et al., 2022). These challenges, compounded by recurrent droughts and floods, reduce crop productivity, increase reliance on costly synthetic fertilizers, and weaken the resilience of smallholder farming systems (Sharma et al., 2025; Sosola et al., 2022).

Addressing these challenges require integrated approaches that enhance soil fertility while building resilience to climatic stress. Legume-based intercropping and crop residue incorporation have emerged as sustainable strategies for improving soil health and nutrient use efficiency in smallholder systems. Legumes such as cowpea (Vigna unguiculata) and pigeon pea (Cajanus cajan) play a vital role in biological nitrogen fixation (BNF), improving nutrient cycling, and promoting synergistic interactions that enhance land productivity and resource use efficiency (Ngwira et al., 2012b; Drinkwater et al., 1998; Giller, 2001). When residues are incorporated into the soil, they further improve soil structure, stimulate microbial activity, and increase soil organic matter, thereby reducing fertilizer dependence and mitigating greenhouse gas emissions (Lal, 2006; Begum et al., 2022; Baloch et al., 2025).

Nitrogen (N) plays a central role in agroecosystem productivity, regulating organic matter decomposition, mineralization, and immobilization processes that determine soil fertility and plant nutrient availability (Koch and Sessitsch, 2024). Incorporation of crop residues tightens N cycling by enhancing microbial efficiency and soil N retention, thereby sustaining soil fertility over time (Breza and Grandy, 2025). The type of residue incorporated strongly influences microbial behaviour and N transformation. Legume residues, characterized by low carbon-to-nitrogen (C:N) ratios, decompose more rapidly and release N more efficiently than high C:N residues, thereby stimulating microbial mineralization and improving nutrient availability (Palm et al., 2001; Toleikiene et al., 2024).

Legume–legume intercropping systems, such as cowpea–pigeon pea combinations, are particularly relevant for improving N dynamics in low-input smallholder farming systems. Nitrogen is often a limiting nutrient in these systems, and intercropping legumes Cowpea–pigeon pea in-Above ground biomass removed after 0–20, 20–40 tercrop (residue removed) harvest provides additional biological N inputs through symbiotic fixation, reducing the need for synthetic fertilizers (Melese et al., 2025; Kebede, 2021). Furthermore, incorporating legume residues enhances microbial biomass and nutrient cycling efficiency, improving plant N uptake and sustaining soil fertility over time (Kumar et al., 2025; Sharma et al., 2025). The complementary rooting structures and microbial associations between cowpea and pigeon pea promote efficient N use and recycling within the soil system (Kokkini et al., 2025).

Despite these benefits, many smallholder farmers in Malawi still rely on monocropping and unsustainable residue management, partly due to limited awareness of the long-term advantages of legume-based systems (Chikowu et al., 2015). Given the increasing frequency of droughts in Malawi’s semi-arid regions, understanding how cowpea–pigeon pea intercropping and residue incorporation affect soil N dynamics is essential. This study, therefore, investigates the effects of cowpea–pigeon pea intercropping and residue incorporation on soil N forms—ammonium (NH4+), nitrate (NO3-), and total N (TN). The objective is to identify sustainable residue and cropping strategies that enhance N availability, reduce N fertilizer dependence, and promote resilient, productive smallholder systems in Malawi’s drought-prone areas.

Study site description

This research was conducted in two distinct locations in Malawi; Chinguluwe EPA located in the central lakeshore district of Salima, and Lunzu EPA situated in the hot, dry, and low-rainfall area of Blantyre in the southern region. Salima District sits at an elevation of 510 meters above sea level and receives an average annual rainfall of approximately 976 mm, with a unimodal distribution. In contrast, Blantyre District has a higher elevation of 1,039 meters above sea level and experiences a mean annual rainfall of 1,122 mm. These sites were chosen due to their distinct agricultural and environmental characteristics, including recurrent dry spells, degraded soils, and low fertility, all of which contribute to reduced crop yields. The cropping history of these areas highlights challenges with staple cereals such as maize and certain legumes, making them particularly suitable for evaluating drought-tolerant crops like pigeon pea, sorghum, millet, and cowpea.

Field experiments were conducted during the 2022/23 and 2023/24 cropping seasons. Treatments were arranged in a randomized complete block design with three replications (Table 1). Five cropping systems were evaluated: (i) sole sorghum, (ii) sole pigeon pea, (iii) sole cowpea, (iv) cowpea–pigeon pea intercrop, and

(v) cowpea–pigeon pea intercrop with residue removal (control). Soil sampling was superimposed on the same plots in the second season in a factorial arrangement with two soil depths (0–20 cm and 20–40 cm).

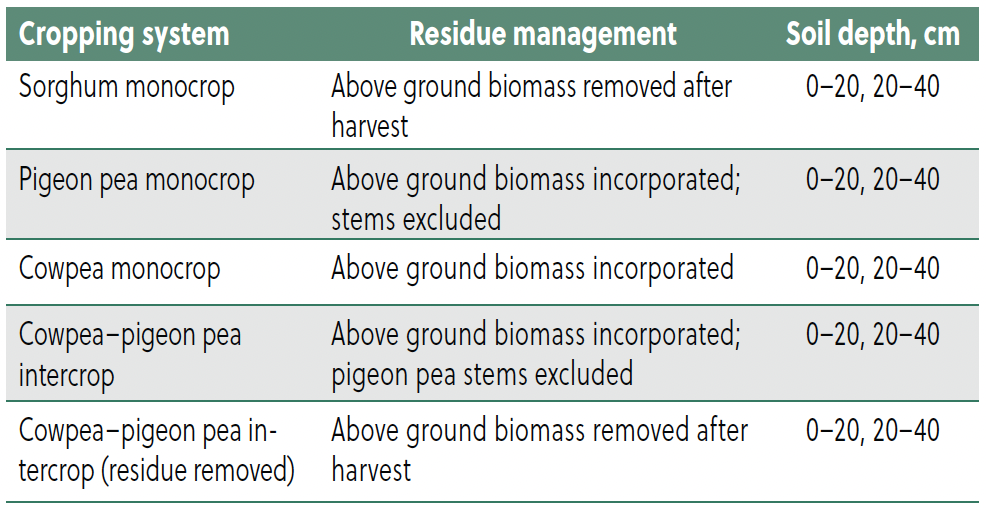

Table 1. Description of experimental treatments and residue management practices.

Residue management varied across treatments. In sole sorghum and the control intercrop, all above ground biomass was removed after harvest. In sole cowpea, sole pigeon pea, and intercrop plots, residues were incorporated into the soil, except pigeon pea stems, which were excluded due to their resistance to decomposition.

Above ground biomass was measured at harvest, and representative samples of cowpea and pigeon pea residues were collected to assess quality prior to incorporation. Samples were oven-dried, ground (<0.5 mm), and analyzed for N and carbon (C). Carbon-to-nitrogen (C:N) ratios were calculated to evaluate residue decomposition potential (Palm et al., 2001). Nutrient uptake was estimated as the product of total above ground dry matter and nutrient concentration.

Soil samples were collected from each plot using an auger at depths of 0–20 cm and 20–40 cm. Composite samples were obtained from three random positions per plot. Sampling was carried out at three stages: (i) immediately after harvest and before residue incorporation, (ii) six months after incorporation, and (iii) at three-week intervals up to nine weeks after planting sorghum in the following season.

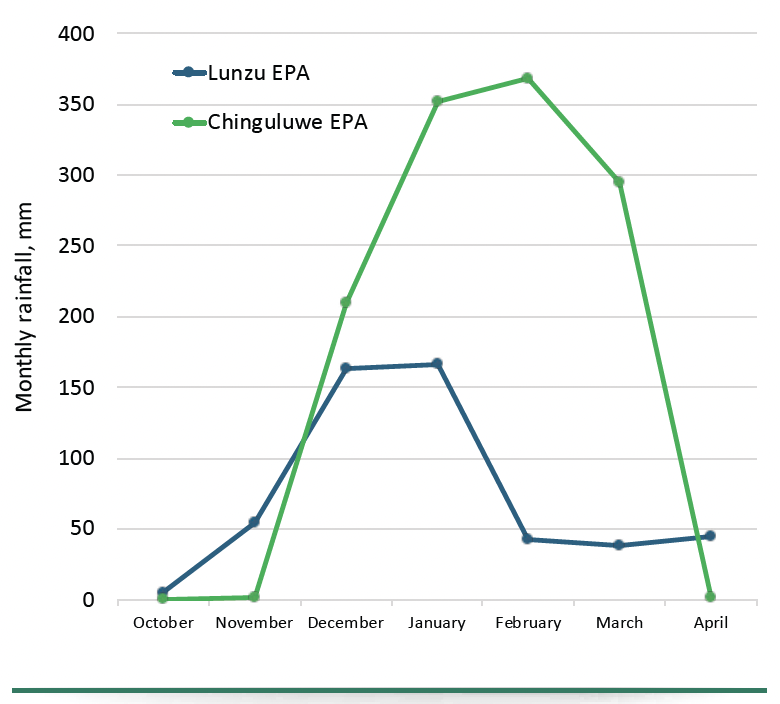

Monthly rainfall at Chinguluwe and Lunzu EPAs

Monthly rainfall patterns at Chinguluwe and Lunzu EPAs during the 2023/24 cropping season showed distinct differences in distribution and intensity (Fig. 1). At Chinguluwe, rainfall was minimal in October and November, sharply increasing in December and peaking at approximately 370 mm in January and February, indicative of a short, intense rainy season.

However, rainfall declined rapidly by April, potentially constraining late-season nutrient mineralization in the latter months and increasing nutrient leaching risks between January and February. In contrast, Lunzu experienced a more gradual rainfall rise from October, peaking moderately around 160–170 mm in December–January, and declining slowly through February and March, with a minor resurgence in April. This extended, moderate rainfall pattern likely facilitated gradual residue decomposition and steady nutrient mineralization, reducing leaching risks and promoting better synchronization between nutrient availability and crop uptake.

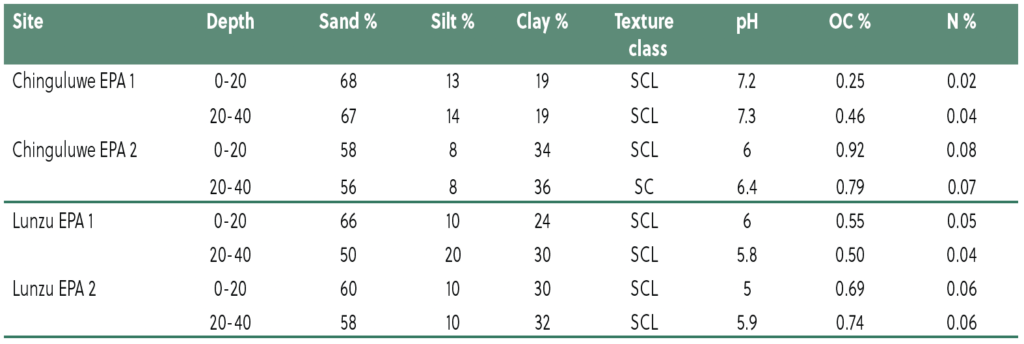

Baseline soil characteristics

Baseline soil analyses revealed variability in texture, pH, organic carbon (OC), and N across sites (Table 2). Lunzu soils were sandy clay loam (SCL) with slightly to moderately acidic pH (5.0–6.0) and low OC (0.50–0.74%) and N (0.04–0.06%). Chinguluwe soils ranged from SCL to sandy clay (SC), with neutral to slightly alkaline pH (6.0–7.3) and more variable OC (0.25–0.92%) and N (0.02–0.08%). These findings suggest that both sites have limited fertility, requiring organic or inorganic amendments to improve SOC and nutrient availability.

Table 2. Baseline soil fertility characteristics at mother on-farm trial at Chinguluwe EPA.

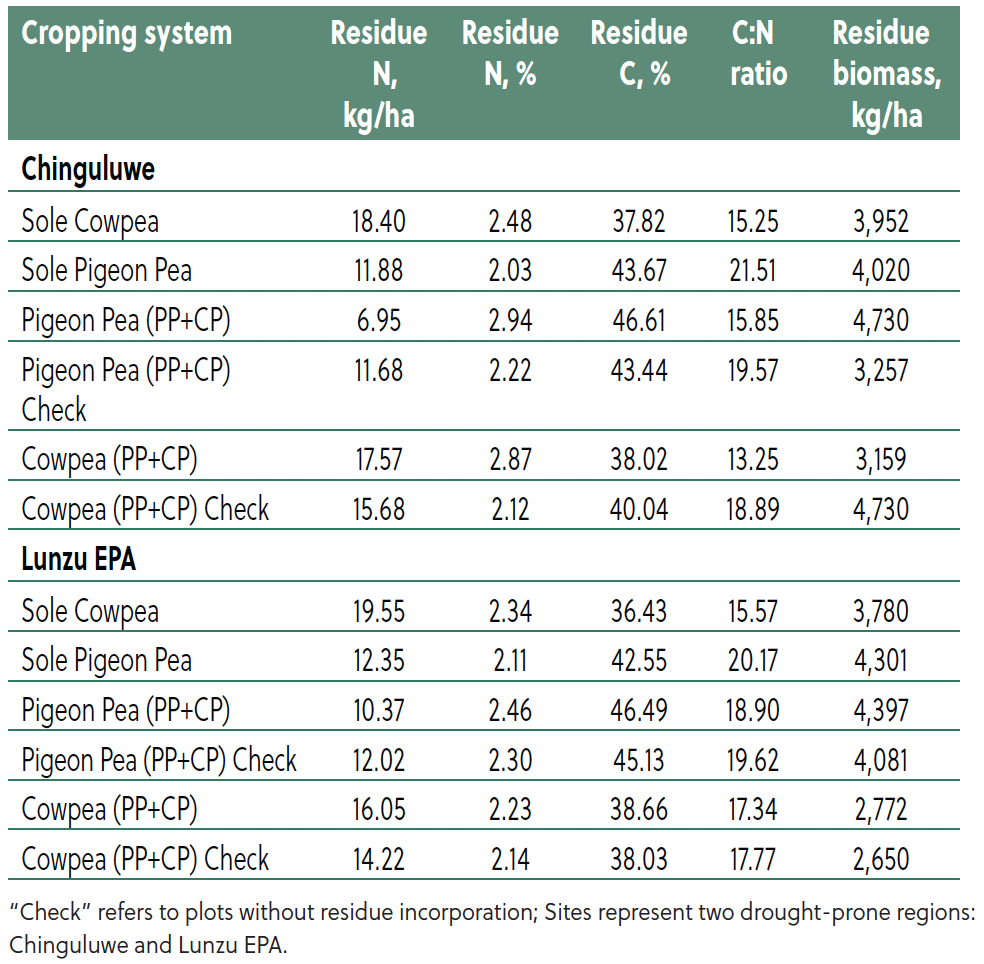

Residue nitrogen composition and biomass production

Crop residue quality and biomass differed significantly among cropping systems (Table 3). Cowpea residues consistently had higher N content and narrower C:N ratios compared to pigeon pea, indicating faster decomposition and nutrient release. For example, at Chinguluwe, sole cowpea residues contained 2.48% N with a biomass yield of 3,952 kg/ha. Sole pigeon pea had 2.03% N with a yield of 4,020 kg/ha and a wider C:N ratio. Intercropping (PP+CP) enhanced residue quality for both species, with cowpea residues showing 2.87% N and a C:N ratio of 13.25, while pigeon pea residues contained 2.94% N and a C:N ration of 15.85. Intercropped pigeon pea produced the most biomass (4,730 kg/ha at Chinguluwe and 4,397 kg/ha at Lunzu), indicating strong potential for SOC build-up and nutrient cycling.

Table 3. Effect of cropping system on residue nitrogen composition and biomass production under cowpea–pigeon pea intercropping.

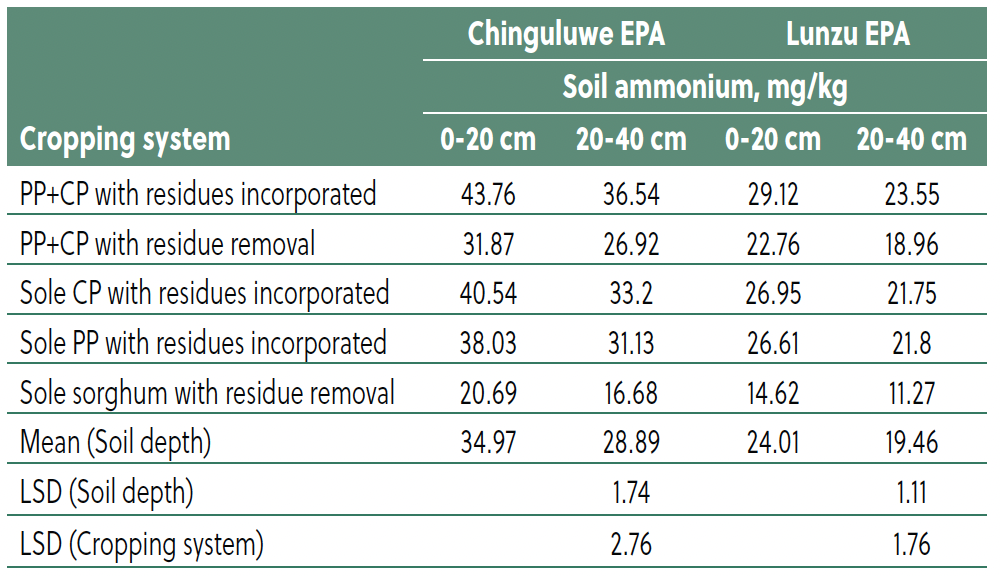

Residue incorporation and soil ammonium

Soil ammonium concentrations were signifcantly infuenced by cropping system and soil depth (Table 4). The PP+CP intercrop with residue incorporation recorded the highest soil profle ammonium at both sites (i.e., mean values calculated across both depths: Chinguluwe: 40.15 mg/kg; Lunzu: 26.34 mg/kg). Sole cowpea and sole pigeon pea with residues also maintained elevated ammonium, but systems with residue removal, especially sole sorghum, had the lowest levels (Chinguluwe: 18.68 mg/kg; Lunzu: 12.95 mg/kg). Ammonium concentrations were consistently higher within the 0-20 cm soil layer compared to the 20-40 cm, reflecting surface accumulation.

Table 4. Effects of cropping system and their residue incorporation on soil ammonium.

Temporal distribution of soil ammonium

Temporal monitoring revealed that residues incorporation led to a gradual increase in ammonium, peaking six months after incorporation (Fig. 2). For instance, the PP+CP intercrop at Luna EPA increased from 22.93 mg/kg pre-incorporation to a peak of 36.55 mg/kg (25.59 to 60.2 ppm at Chinguluwe). Following this, ammonium levels declined slowly but remained above initial concentrations, indicating sustained N release. Systems without residue incorporation showed minimal increases.

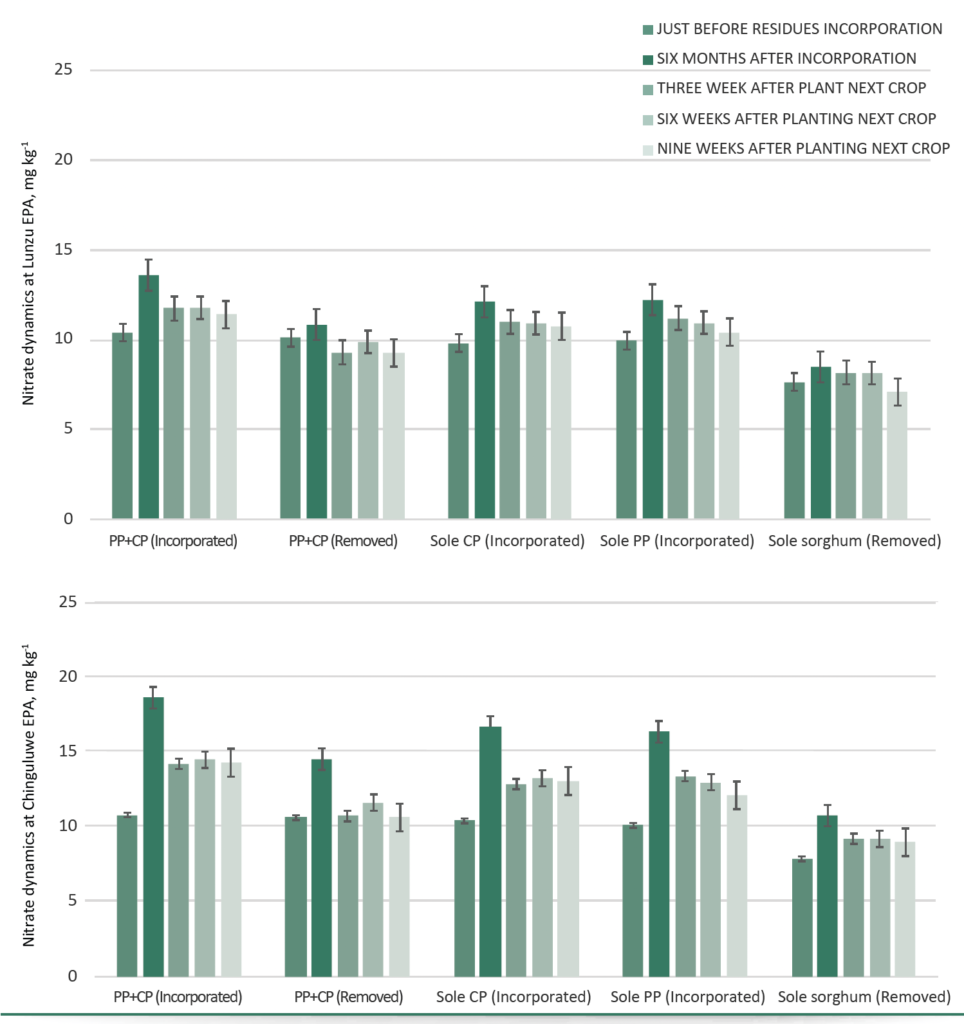

Residue incorporation and soil nitrate

Residue incorporation also significantly enhanced residue quality for both species, with cowpea soil nitrate levels (Table 5). The PP+CP intercrop with residues showing 2.87% N and a C:N ratio of 13.25, residues recorded the highest nitrate concentrations at while pigeon pea residues contained 2.94% N and a both sites (Chinguluwe: 12.97 mg/kg; Lunzu: 10.57 C:N ratio of 15.85. Intercropped pigeon pea produced mg/kg), whereas the same system without residue the most biomass (4,730 kg/ha at Chinguluwe and incorporation had lower levels (Chinguluwe: 10.62 4,397 kg/ha at Lunzu), indicating strong potential for mg/kg; Lunzu: 8.99 mg/kg). Sole sorghum consistently SOC build-up and nutrient cycling. showed the lowest nitrate levels, reflecting limited contribution to soil N. Nitrate concentrations were higher at 0-20 cm than 20-40 cm, with a significant interaction between soil depth and cropping system, highlighting depth-dependant effects of residue management.

Table 5. Effects of cropping system and their residues management on soil nitrate.

Temporal nitrate dynamics

Over time, nitrate peaked six months after residue incorporation (Chinguluwe: 18.65 mg/kg; Lunzu: 13.60 mg/kg) and declined gradually during subsequent crop growth (Fig. 3). Residue-incorporated systems maintained nitrate above pre-incorporation levels, whereas systems with residue removal exhibited persistently lower nitrate, emphasizing the role of incorporating high N organic matter sources in sustaining soil N availability.

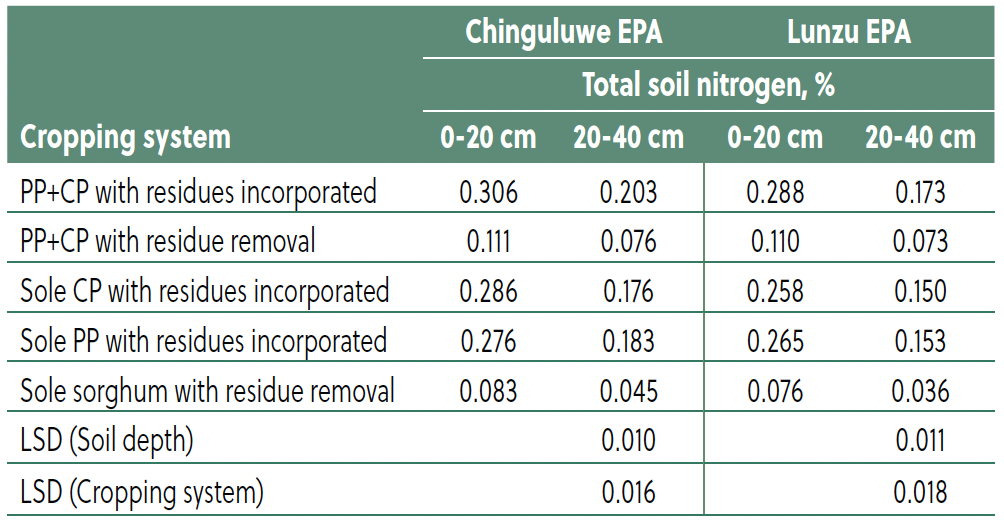

Residue incorporation and total nitrogen

Cropping system, residue management, and soil depth significantly influenced total nitrogen (TN) (Table 6). The PP+CP intercrop with residue incorporation consistently recorded the highest TN across both sites (Chinguluwe: 0.306% at 0–20 cm, 0.203% at 20–40 cm; Lunzu: 0.288% and 0.173%, respectively), followed by sole cowpea and sole pigeon pea with residues. Residue removal systems, including sole sorghum, showed the lowest TN, with values declining over time (e.g., PP+CP residue removal: Chinguluwe 0.111% at 0–20 cm). Total N was significantly higher at 0–20 cm compared to 20–40 cm, confirming the importance of surface residues in maintaining N content.

Table 6. Effects of cropping system total soil nitrogen (%) at Chinguluwe EPA and Lunza EPA.

Intercropping, residue incorporation and soil nitrogen dynamics

The results indicate that legume-based intercropping, particularly when coupled with residue incorporation, markedly improves soil N pools. Incorporation of legume residues with low C:N ratios accelerated mineralization and elevated ammonium concentrations, especially in pigeon pea–cowpea systems, where the combined effects of BNF and residue quality enhanced nutrient release (Fuchs et al., 2024; Njira et al., 2017). These findings highlight the pivotal role of residue quality in regulating N cycling (Yan et al., 2020).

Residue incorporation also significantly increased nitrate concentrations compared with residue removal, demonstrating the contribution of decomposed N-rich organic residues to soil fertility (Palm et al., 2001). Nitrate stratification in the 0–20 cm surface layer corresponded with zones of intense microbial and root activity. Vertical stratification concentrated microbial transformations in the top layer (0–20 cm), with nitrate accumulation linked to microbial hotspots (Zhang et al., 2024). Similarly, ammonium and nitrate retention peaked in the top layer (0–20 cm), consistent with enhanced microbial activity and root density under deep subsoiling (Gu et al., 2025). Notably, nitrate and ammonium levels peaked six months after residue incorporation, followed by declines due to plant uptake, leaching, and denitrification (Chen et al., 2014).

Increases in TN further confirm the benefits of intercropping with residue incorporation. Gains are mainly driven by BNF and microbial decomposition, supporting the use of residue incorporation as a sustainable long-term fertility strategy (Abbasi et al., 2015a). Conversely, residue removal led to stagnation or declines in TN, underscoring N-rich residues as vital nutrient inputs in resource-limited systems (Coulibaly et al., 2020).

Residue chemistry strongly influenced decomposition patterns. Legume residues, characterized by low C:N ratios and high N content, decomposed rapidly, leading to faster mineralization (Nicolardot et al., 2001; Palm et al., 2001; Nyabami et al., 2023). Cowpea residues exemplified this. Microbial activity is most efficient when residues approach a 24:1 C:N ratio. High C:N inputs induce immobilization as microbes scavenge soil N, whereas low C:N residues promote mineralization through surplus N release (Gaudel et al., 2024; USDA NRCS, 2011; Mittal, 2011). Incorporating high-quality residues, such as cowpea and pigeon pea, increased TN by stimulating microbial turnover and decomposition (Abbasi et al., 2015b). The positive effects of residue incorporation were amplified in intercropping systems. Legume-based intercrops enriched rhizosphere ammonium and nitrate through BNF and microbial stimulation, thereby improving N availability in such low-input systems (Mokgethoa, 2024). Intercropping also raised soil TN, ammonium, and nitrate concentrations by 14.5% compared to monocropping, while enhancing microbial diversity, (Zhang et al., 2024; Bichel et al., 2017). These outcomes validate intercropping as a sustainable intensification strategy that enhances root-zone utilization and strengthens soil fertility and resilience (Qiu et al., 2025). Residue incorporation consistently outperformed residue removal, with reports of mineral N increasing up to 1.23-fold (Bakht et al., 2009) and TN improving the concentration to between 0.066–0.098% across the 0–20 cm soil layer (Pu et al., 2019). Such improvements extend beyond immediate nutrient cycling, contributing to long-term soil chemical enhancement (Coulibaly et al., 2020).

Overall, the evidence demonstrates that integrating residue incorporation into legume-based intercropping systems improves N cycling via synergistic effects of BNF, residue quality, and microbial processes. This combined approach not only enhances short-term nutrient availability but also builds long-term fertility and resilience, making it a promising strategy for sustainable intensification in smallholder farming systems.

Recommendations

1. Promote Legume–Legume Intercropping Systems – Smallholder farmers should be encouraged to adopt cowpea–pigeon pea intercropping as a practical and sustainable strategy for improving N cycling and soil fertility. This system enhances BNF, increases residue N content, and contributes organic matter inputs, thereby improving soil structure, water retention, and nutrient availability.

2. Encourage Residue Retention and Incorporation – Residue incorporation should be prioritized over removal or burning, as it ensures continuous N release, enriches soil organic matter, and supports long-term nutrient accumulation. Extension services should provide training on appropriate methods and timing of residue incorporation to maximize N mineralization and soil improvement.

3. Integrate Intercropping and Residue Management into Climate-Smart Agriculture (CSA) Strategies – Policymakers and agricultural development programs should embed legume-based intercropping and residue management within Malawi’s national CSA framework. This integration will strengthen soil fertility, reduce dependence on inorganic fertilizers, and enhance resilience to drought and land degradation.

4. Support Research and Long-Term Monitoring – Further research is needed to assess the long-term effects of legume– legume intercropping and residue incorporation on soil N dynamics, organic C accumulation, and yield sustainability under diverse climatic and soil conditions. Expanding on-farm participatory trials will help refine and adapt intercropping models to local contexts.

Summary

This study demonstrates that cowpea–pigeon pea intercropping, when combined with residue incorporation, is an effective and climate-smart strategy for enhancing N dynamics and improving soil fertility in Malawi’s drought-prone smallholder farming systems. The results revealed that intercropping significantly improved residue quality, while increased residue quantity contributed greater biomass and long-term N stabilization. Legume–legume intercropping enhances BNF, residue N enrichment, and soil nutrient cycling efficiency, ultimately leading to improved soil fertility and crop productivity.

Furthermore, the study established that residue incorporation plays a pivotal role in sustaining N availability by promoting gradual mineralization and reducing nutrient losses. Systems that retained and incorporated residues exhibited markedly higher soil ammonium, nitrate, and total N levels compared to residue removal systems. This highlights the importance of maintaining organic matter inputs to support nutrient release, stimulate microbial activity, and restore long-term soil fertility.

Overall, the findings underscore that cowpea–pigeon pea intercropping with residue incorporation offers a low-cost, sustainable, and scalable pathway for rebuilding soil N stocks, enhancing productivity, and strengthening climate resilience in Malawi’s smallholder systems. By reducing dependence on synthetic fertilizers, improving N use efficiency, and sustaining soil fertility, this integrated approach provides a practical solution for advancing agricultural sustainability and ensuring food security in drought-affected regions. n

Acknowledgement

The authors hereby acknowledge the African Plant Nutrition Institute (APNI) and the Norwegian Directorate for Higher Education and Skills (Hk-Dir) for supporting the study through the Phosphorus Fellowship and NORPART-2021/10543 project respectively and the Government of Malawi through the Ministry of Agriculture for making available field staff and farmer networks for the study.

Mr. Nthewa (charlesharrynthewa@gmail.com) is with Lilongwe University of Agriculture and Natural Resources, Malawi and Department of Agricultural Research Service, Ministry of Agriculture, Malawi. Dr. Njira, Prof. Nalivata and Assoc. Prof. Chimungu are with Lilongwe University of Agriculture and Natural Resources, Malawi. Dr. Phiri, One Planet Laureate, is with the Department of Agricultural Research Service, Ministry of Agriculture, Malawi.

Cite this article

Nthewa, C.H., Njira, K., Nalivata, P., Chimungu, J., Phiri, A.T. Nitrogen Dynamics under Cowpea–Pigeon Pea Intercropping and Residue Management in Malawi’s Drought Prone Areas. Growing Africa 4(2):46-54.

https://doi.org/10.55693/ga42.GKKF6759

REFERENCES

Abbasi, M.K., et al. 2015a. Impact of the addition of different plant residues on nitrogen mineralization–immobilization turnover and carbon content of a soil incubated under laboratory conditions. Solid Earth, 6, 197–205.

Abbasi, M.K., et al. 2015b. Nitrogen mineralization and carbon dynamics as affected by residue quality and soil type. Soil Bio. Biochem., 80, 174–185.

Bakht, J., et al. 2009. Influence of crop residue management, cropping system and N fertilizer on soil N and C dynamics and sustainable wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) production. Soil & Tillage Res., 104, 233–240.

Bichel, A., et al. 2017. Impact of residue addition on soil nitrogen dynamics in intercrop and sole crop agroecosystems. Geoderma, 304, 12–18.

Breza, L.C., Grandy, A.S. 2025. Organic amendments tighten nitrogen cycling in agricultural soils: A meta-analysis on gross nitrogen flux. Frontiers in Agron., 7, 1472749.

Chen, B., et al. 2014. Soil nitrogen dynamics and crop residues: A review. Agron. for Sus. Dev., 34(2), 429–442.

Coulibaly, S.S., et al. 2020. Incorporation of Crop Residues into Soil: A Practice to Improve Soil Chemical Properties. Agric. Sci., 11, 1186–1198.

Drinkwater, L.E., et al. 1998. Legume-based cropping systems have reduced carbon and nitrogen losses. Nature, 396(6708), 262–265.

Fuchs, K., et al. 2024. Intercropping legumes improves long.term productivity and soil carbon and nitrogen stocks in sub-Saharan Africa. Global Biogeochem. Cycl., 38, e2024GB008159.

Gaudel, G., et al. 2024. Soil microbes, carbon, nitrogen, and the carbon to nitrogen ratio indicate priming effects across terrestrial ecosystems. J. Soils and Sediments, 24(1), 307–322.

Giller, K.E. 2001. Nitrogen fixation in tropical cropping systems (2nd ed.). CAB International.

Kebede, E. 2021. Contribution, utilization, and improvement of legumes-driven biological nitrogen fixation in agricultural systems. Front. Sus. Food Sys., 5, 767998.

Koch, H., Sessitsch, A. 2024. The microbial-driven nitrogen cycle and its relevance for plant nutrition. J. Exp. Botany, 75(18), 5547–5556.

Kumar, T.S., et al., 2025. Residual effect of summer legumes incorporation on soil nutrient status and nutrient use efficiency of kharif rice. Front. in Sus. Food Sys., 9, 1535162.

Lal, R. 2006. Managing soils for feeding a global population of 10 billion. J. Sci. Food and Agric. 86(15), 2273–2284.

Melese, M., et al., 2025. Legume integration in smallholder farming systems for food security and resilience to climate change. PLOS ONE, 20(8), e0327727.

Mokgethoa, M.M. 2024. Effects of Maize and Legume Intercropping System on Soil Nitrogen Dynamics. Master’s Thesis, University of Limpopo. http://ulspace.ul.ac.za/ handle/10386/4836

Ngwira, A., et al. 2012a. Conservation agriculture systems for improving soil fertility and productivity. Agric. Sys., 113, 7–14.

Ngwira, A.R., et al. 2012b. On-farm evaluation of yield and economic benefit of short-term maize legume intercropping systems under conservation agriculture in Malawi. Field Crops Res., 132, 149–157.

Nicolardot, B., et al. 2001. Simulation of C and N mineralisation during crop residue decomposition: A simple dynamic model based on the C:N ratio of the residues. Plant Soil, 228, 83–103.

Njira, K., et al. 2017. Effects of legume residues on nitrogen dynamics in smallholder farming systems. Malawi Journal of Agriculture, 15(1), 45–52.

Nyabami, P., et al. 2023. Nitrogen release dynamics of cover crop mixtures in a subtropical agroecosystem were rapid and species-specific. Plant Soil 492, 399-412.

Palm, C.A., et al. 2001. Organic inputs for soil fertility management in tropical agroecosystems: Application of an organic resource database. Agric., Ecosys. Environ., 83(1–2), 27–42.

Pu, C., et al. 2019. Residue management induced changes in soil organic carbon and total nitrogen under different tillage practices in the North China Plain. J. Integrative Agric., 18(6), 1337–1347.

Qiu, Y., et al. 2025. Advances in Water and Nitrogen Management for Intercropping Systems. Agron., 15(8), 2000.

Sharma, N., et al., 2025. Legumes in cropping system for soil ecosystem improvement: A review. Legume Res., 48(1), 01–09.

USDA NRCS. 2011. Carbon to nitrogen ratios in cropping systems. USDA NRCS. https://www.nrcs.usda.gov/Internet/FSE_ DOCUMENTS/nrcseprd331820.pdf

Yan, X., et al. 2020. Carbon-to-nitrogen ratios of crop residues and their effects on soil nitrogen availability. Soil Till. Res., 203, 104696.

Zhang, Y., et al. 2024. Maize/Soybean Intercropping with Nitrogen Supply Levels Enhances Soil Nitrogen Fractions and Microbial Diversity. Front. Plant Sci., 15, 1437631.