By Peter Mbogo Mfune, Joseph Chimungu, Keston Njira, Patson Nalivata, and Austin T. Phiri

Researchers focused on the short-term effects of legume planting pattern and residue management practices (i.e., incorporation immediately after harvest and mulching) on soil fertility status in contrasting environments and soils in Malawi. Results revealed substantial increase in soil nitrogen and phosphorus which would eventually improve soil health and reduce mineral fertilizer requirements for subsequent crops.

Soil fertility decline has been reported to be one of the major challenges faced by smallholder farmers in Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) (Zingore et al., 2015). In Malawi, like other SSA countries, high population has put great pressure on agricultural land. This has resulted in the loss of soil fertility due to poor soil management practices such as monocropping coupled with under replenishment of nutrients removed with harvested crop products (Zingore et al., 2015). Although inorganic fertilizers increase crop yields, they continue to be expensive and are often beyond reach for most farmers (World Bank, 1996). Governments try to put measures such as input subsidies in place to increase fertilizer use, but the sustainability of such initiatives is often unpredictable. It is imperative to search for alternative means of enhancing soil fertility that are both sustainable and economic. One such approach is Integrated Soil fertility Management (ISFM), which combines soil fertility management practices that promote use of both organic and inorganic nutrient sources, improved germplasm, and appropriate agronomic practices tailored to local conditions to maximize agronomic use efficiency of all applied nutrients, and improve overall crop productivity (Vanlauwe et al., 2010). One such ISFM practice includes the integration of legumes within the crop production system (Palm et al.,1997).

Leguminous crops have the capacity to increase soil fertility through biological nitrogen fixation (BNF) and subsequent mineralization of below and above ground biomass (Drinkwater et al., 1998). BNF is achieved through the mutualistic relationship between legumes and bacteria, especially rhizobia spp including: Allorrhizobium, Bradyrhizobium, Rhizobium, Sinorhizobium, and Mesorhizobium (Giller, 2001; Syvia et al., 2005; Berrada and Fikri-Benbrahim, 2014). Soil microorganisms decompose the highly nutrient-rich plant residues that enrich the soil with much-needed N and other essential nutrients. Usually about two-thirds of the N fixed through a legume crop is available for the subsequent growing season. Microorganisms can positively affect physical, chemical, and biological soil properties that are the defining facets of soil health (Stagnaria et al., 2017; Nanganoa et al., 2019; Vasconcelo et al., 2020). Legume crop products also contribute to human and livestock nutrition as low-cost sources of protein, especially to resource poor farmers where meat availability is low (Maposa and Jideani, 2017; Kerr et al., 2007).

In Malawi, traditional legumes include common beans (Phaseolus vulgaris), cowpea (Vigna ungiculata), soybean (Glycine max), groundnut (Arachis hypogaea) and pigeon pea (Cajanus cajan) grown as either sole crops or as intercrops with cereals like maize (Mhango et al., 2012; Ngwira et al., 2012). Sole legume systems contribute to nutrient inputs primarily through N fixation, while intercropping systems not only enhance land-use efficiency but also foster complementary resource use between species.

Some farmers intercrop legumes with other legumes, a practice commonly called double-up legume (DUL) cropping (ICRISAT/MAL, 2000; Mhango, 2011). The goal of this strategy is to take advantage of two complimentary interactions higher than cowpea (62.5 kg N/ha) or pigeon pea (59.9 kg N/ha) when intercropped with maize, but it was comparable to that of the pigeon pea alone (92.9 kg N/ha). Furthermore, (Kanyama-Phiri et al., 2000; Phiri et al., 2012) reported that farmers in Malawi consistently ranked DUL highly among organic soil fertility enhancement options. To maximize soil fertility benefits under DUL, legume residue management becomes very critical. Residue management plays a key role in sustaining nutrient stocks by recycling organic matter and maintaining soil cover, thereby reducing erosion and nutrient loss (Sanginga and Woomer, 2009).

Therefore, short-term evaluations of these practices are particularly critical to understand immediate impacts on soil fertility parameters such as soil organic carbon (C), available N and P, and soil biological activity. Despite their potential, the relative short-term benefits of these systems remain underexplored in many smallholder contexts. This study investigates the short-term effects of sole legume cropping, legume-legume intercropping, and residue management on soil fertility, providing insights to guide ISFM strategies for sustainable intensification in SSA.

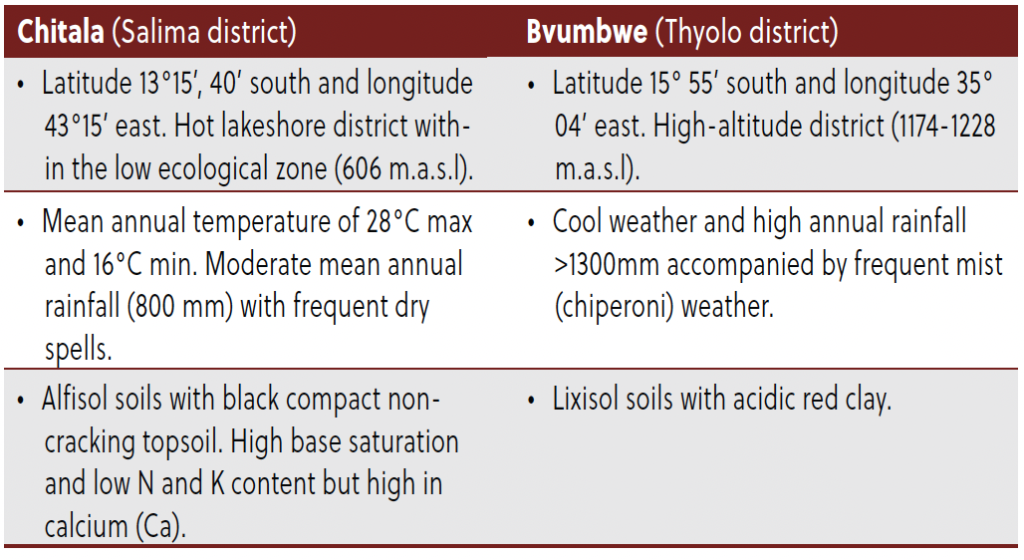

Study site description

The study was carried out at two distinct sites including Chitala agricultural research station within the Chinguluwe extension planning area in the Central region and Bvumbwe agricultural research station under the Dwale extension planning area in the South.

The experiment was a randomized complete block design with all the five treatments replicated three times. Each plot size was 20 x 10 m. The pigeon pea crop was planted at a spacing of 90 cm apart with three seeds per station in both sole and intercropped treatments.

Cowpea in both sole and intercropped treatments was planted at 30 cm apart with three seeds planted per station according to MoAFS (2012). Sorghum seeds were planted at 30 cm (5-7 seeds) per planting station then thinned to two plants after emergence (88,888 plant population). At harvest time all legume biomass from the treatments were incorporated into the soil except in treatment 5 (mulch) in accordance with design.

The crop varieties included: pigeon pea (Mwaiwathu alimi, ICEAP 00557) maturing between 5-6 months with yields up to 2.5 t/ha, cowpea (IT82-E-16) maturing in 2 months with yields up to 3 t/ha, and sorghum (Pilira 5).

All good agronomic practices were applied across treatments during the whole growing season. The feld was deeply ploughed by tractor to minimize the efect of hardpans on root penetration. Hand hoe ridging was used to efectively achieve the recommended 75 cm ridge spacing. Planting was done in late December at both sites after receiving their efective rainfall. Manual weeding was used at both sites to make sure that the trials are free of weeds. Scouting of pests, especially leaf eaters and sap suckers, was done every two weeks and pests were treated as needed. At harvest, all the biomasses were cut and incorporated into the soil between the ridges. Soil sampling was done 10 weeks after biomass incorporation to determine fixed and mineralized nutrients.

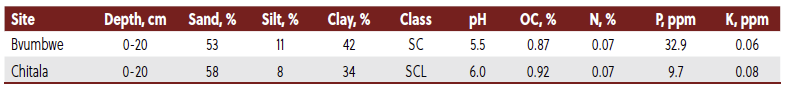

Baseline soil characterization

Table 1 provides the soil baseline data at the two trial sites for the season 2021-2022 before legume planting. At Chitala, the soil texture was sandy clay loam (SCL). The Bvumbwe soil was sandy clay (SC). Soil pH was 6.0 and 5.5 for Chitala and Bvumbwe, respectively. Both sites had very low levels of N (<0.08%). Chitala had low levels of P (9-18 ppm range) while Bvumbwe had adequate P (25-33 ppm range) according to threshold values.

Table 1. Baseline composite soil characteristics for Bvumbwe and Chitala.

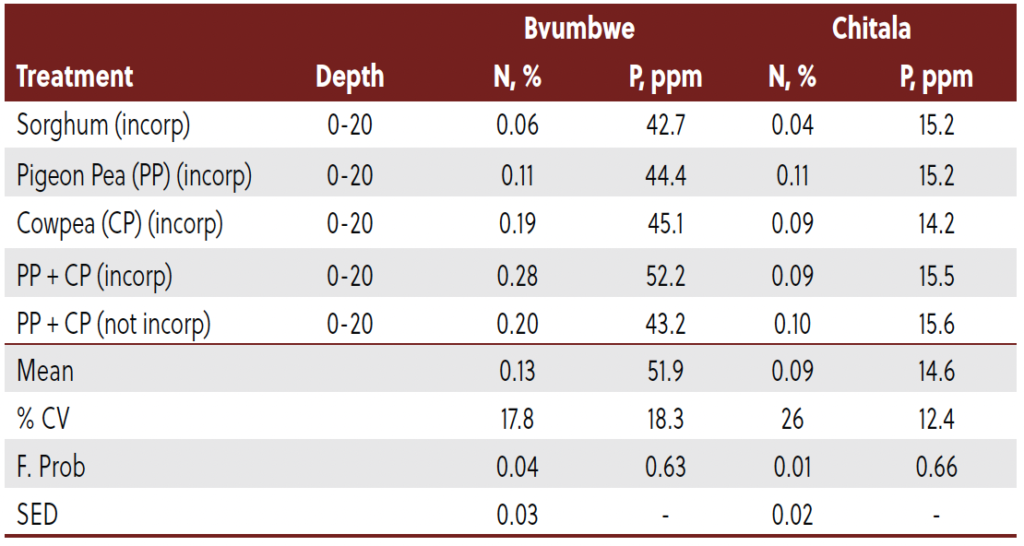

Effect of legume cropping system on soil nitrogen and phosphorus

Table 2 shows soil N and P concentrations after legume harvesting at both trial sites. At Bvumbwe, low levels of N (0.08-0.12% range) were found for the pigeon pea system while the sorghum system had very low (<0.08%) N levels. No significant differences were found between cowpea cropping and pigeon pea + cowpea (biomass not incorporated) systems, which both had medium N levels (0.12-0.2% range). The system with pigeon pea + cowpea biomass incorporated had high levels of N (0.20-0.3%). Soil P also differed across treatments at Bvumbwe although all had very high P levels (>34 ppm). The pigeon pea + cowpea (biomass incorporated) system had the highest P levels (52.2 ppm).

Table 2. Soil nitrogen and phosphorus afer legume cropping system at Bvumbwe and Chitala trial sites.

At Chitala, significant differences in soil N and P were also obtained amongst the cropping systems. Sole sorghum cropping had very low N levels (<0.08%) compared to the other treatments which were slightly higher (0.08-0.12% range). Pigeon pea cropping had higher levels of N (0.11%) compared to the other cropping systems. Significant differences were also obtained in soil P across the treatments although all were categorized as low (9-18 ppm range). The pigeon pea+cowpea (PP+CP) treatment (biomass not incorporated) had the highest P levels (15.6 ppm).

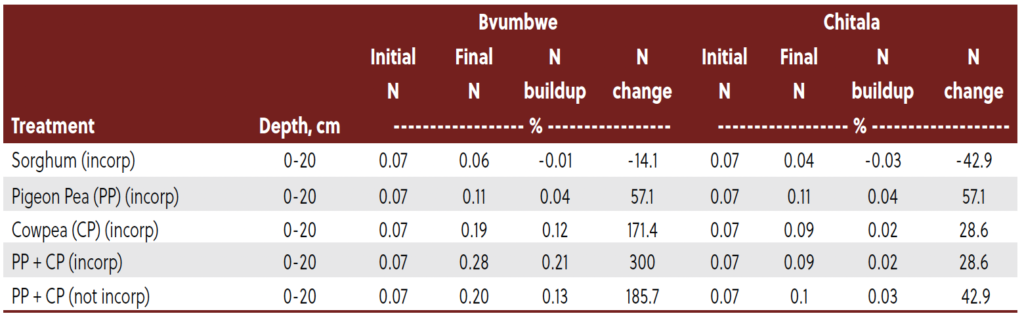

Soil nitrogen and phosphorus build-up

Table 3 shows the overall effect of legume cropping system on N buildup at both sites. Results from Bvumbwe indicate that PP+CP biomass incorporated had the greatest positive buildup in N levels (0.21%) representing a 300% increase over baseline samples. The sole sorghum system had the lowest levels (0.06%) representing a 14.1% decline in N. No significant differences in N levels were observed between sole cowpea (0.19%) and PP+CP biomass not incorporated (0.20%) representing respective increases of 171.4 % and 185.7%. The difference in N buildup between the two PP+CP systems (incorporated vs. not incorporated) demonstrated the impact of residue management.

Table 3. Effect of cropping system on soil nitrogen buildup.

At Chitala, sole pigeon pea had the highest N buildup (0.11%) though not statistically different to PP+CP biomass incorporated (0.09%) and pigeon pea biomass not incorporated (0.10%) representing increases of 57.1%, 28.6%, and 42.9%, respectively. Like Bvumbwe, sole sorghum grown at Chitala had the lowest levels of N (0.04%), representing a decline of -42.9%.

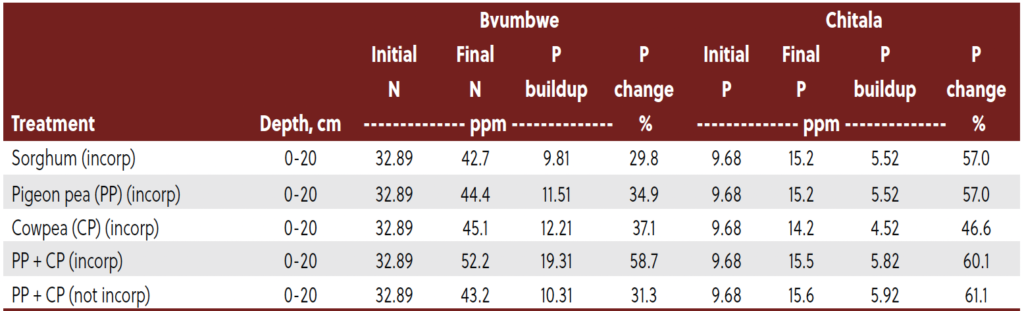

Table 4 below indicates the effect of legume cropping systems on P buildup at both sites. Significantly higher P buildup (19.3 ppm) was recorded under the PP+CP (biomass incorporated) system at Bvumbwe. Phosphorus buildup at Chitala was generally lower, PP+CP biomass not incorporated (5.92 ppm) had the highest P buildup to PP+CP biomass incorporated (5.82 ppm) representing a 61.1% and 60.1% change respectively. Insignificant differences in P change were observed with other cropping system at both sites but sole sorghum had the lowest change (29.8%) at Bvumbwe while sole cowpea was the lowest (46.6%) at Chitala.

Table 4. Effect of cropping system on soil nitrogen buildup.

Significantly higher N and P buildup in legume inclusive systems signify the positive short-term effects this cropping system had on major soil fertility defining parameters. These increases under DUL treatments, where residues were incorporated in the soil immediately after harvesting, clarify the significance of residue management in legume cropping system. These results support the hypothesis that residue management in either sole legume or DUL systems affects soil fertility differently under different environments. Pigeon pea + cowpea where biomass was incorporated had a higher N and P contribution at the Bvumbwe site, while at Chitala sole pigeon pea contributed higher N while PP+CP biomass not incorporated registered the highest P levels.

Baseline soil N showed low levels of this nutrient at both sites. This gave a good standpoint for this study as initial amounts of N in the soil affect subsequent N fixation. Such an understanding agrees with Havlin et al., 2005 who reported that excess nitrite in the soil reduces the activity of nitrogenase thereby reducing N fixation.

However, other differences between sites are suggested to have affected the performance of different cropping systems tested in this study as the same treatments performed differently across sites. This agrees with the findings of Giller, 2001; Mozamadi et al., 2012 who reported that growth, nodulation and BNF of legumes are affected by many factors which include soil temperature, soil pH, essential macro and micronutrients, presence of essential microbial symbionts, and the cropping system practiced. It is therefore important to consider differences in environmental conditions when practicing legume-based cropping system. Acidic and moderately acidic soil pH observed at both sites did not have an apparent affect on availability and abundance of microbes effecting nutrient buildup in the soil. A pH between 5.5-7.0 is ideal for enhancing soil nutrient availability to crops as it creates a good environment for microbes to thrive (Hamza, 2008).

At both sites legume cropping systems positively affected N and P buildup, which affirms the effectiveness of this novel system towards soil improvement. These findings agree with Olufowote and Barnes-McConnel (2002) who reported that when legumes like cowpea are included in a cropping system as either sole or intercrop components, they help to improve fertility status of degraded soils.

The highest N buildup of up to 300% at Bvumbwe in PP+CP (biomass incorporated) can be attributed to combined biomass decomposition and N fixation from both legumes in addition to adequate moisture in the soil, which favors effective decomposition of crop residues. These results agree with the findings of Phiri et al., 2024 who also found that PP+CP increased N and P availability in the soil due to combined effect of the two legumes when compared to growing as sole crops. Lower N and P buildup under non-incorporated (mulched) treatments could be because of dry conditions within the topsoil. The significance of residue incorporation observed in this study agrees with the findings of Bakht et al., 2009 and Shafi et al., 2007 who also reported significant N and P increase in the soil due to legume residue incorporation.

Vigorous pigeon pea growth observed in the field, coupled with a longer duration in the field compared to cowpea, promotes higher N and P buildup in the soil under sole pigeon pea cropping at Chitala as compared to the other treatments studied. This prompted accumulation of more above and below ground biomass, which released more N and P during their decomposition. It was further suggested that the more N and P buildup under sole pigeon pea, as opposed to an intercrop, at Chitala was due to reduced inter-specific competition for light, nutrients, and moisture. Such findings in this study agree with those of Njira et al., 2017 who reported a higher N fixation using the modified N-difference method in sole pigeon pea as compared to a PP+CP intercrop. However, such findings do not agree with this study’s results at Bvumbwe where pigeon pea-cowpea intercropping had higher N buildup compared to sole pigeon pea. This discrepancy is attributed to poor field performance of pigeon pea due to differences in environmental conditions. Negative N buildup under farmers practice (sole sorghum) was attributed to nutrient mining. Slightly lower P buildup under sole cowpea at Chitala was attributed to poor field performance of the crop. Continuous cropping results into mining of available nutrients in the soil thereby rendering the soil being poorer. Such understanding agrees with the findings of Ahmad et al., 2013 who reported that mono-cropping system negatively affects soil physical, chemical, and biological properties.

Conclusions

Double-up legume cropping systems played a significant role in soil nutrient buildup as significant N and P was built under this system compared to other cropping systems. However, environmental conditions including soil types and climate greatly contributed to the effect of these double-up cropping systems. It is imperative to consider site differences when employing different legume cropping systems. The study further explained that nutrient buildup under double-up legume cropping systems is highly intensified with residue incorporation. Farmers are therefore encouraged to adopt this technology to revitalize their soils by increasing nutrients buildup and overall soil health which will eventually reduce the requirement of inorganic fertilizers.

Acknowledgement

The authors hereby acknowledge the African Plant Nutrition Institute (APNI) and the Norwegian Directorate for Higher Education and Skills (Hk-Dir) for supporting the study through the Phosphorus Fellowship and NORPART-2021/10543 project respectively and the Government of Malawi through the Ministry of Agriculture for making available field staff and land at agricultural research stations for the study.

Mr. Mfune (p.mfune@yahoo.co.uk) is with the Department of Agricultural Research Services, Bvumbwe Agricultural Research Station Limbe, Malawi. Prof. Chimungu , Assoc. Prof. Njira and Prof. Nalivata are with Lilongwe University of Agriculture and Natural Resources, Lilongwe, Malawi, Dr. Phiri, One Planet Laureate, is with the Department of Agricultural Research Services, Lunyangwa Agricultural Research Station, Mzuzu, Malawi.

Cite this article

Mfune, P.M., Chimungu, J., Njira, K., Nalivata, P., and Phiri, A.T. 2025. Short-term Effects of Legume-based Cropping Systems and Residue Management on Soil Fertility in Malawi. Growing Africa 4(2):40-45. https://doi.org/10.55693/ga42.DHKX4487

REFERENCES

Ahmad, I., et al. 2013. Effect of pepper-garlic intercropping system on soil microbial and bio-chemical properties. Pak. J. Bot. 45(2):695–702

Bakht, J. et al. 2009. Influence of crop residue management, cropping system and N fertilizer on soil N and C dynamics and sustainable wheat (Triticum aestivum) production. Soil Tillage Res. 104:233–240

Berrada, H., Fikri-Benbrahim, K. 2014. Taxonomy of the rhizobia: current perspectives. British Microbio. Res. J. 4(6), 616-639. Chikowo, R. et al. 2015. Double up legume technology in Malawi boosts and productivity. Africa Rising Brief, 37. Drinkwater, L.E., et al. 1998. Legume-based cropping systems have reduced carbon and nitrogen losses. Nature, 396(6708), 262-265. Giller, K.E. 2001. Nitrogen Fixation in Tropical Cropping Systems, CABI International, Wallingford, UK, pp.150-15.

Hamza, M.A. 2008. Understanding Soil Analysis Data, Department of Primary Industries and Regional Development, Western, Perth, Australia.

Havlin, J.L., et al. 2005. Soil Fertility and Fertilizers: an introduction to nutrient management. 7th (ed.). Pearson Prentice Hall, New Jersey pp. 98-144.

ICRISAT/MAI. 2000. Cost-effective Soil Fertility Options for Smallholder Farmers in Malawi. ICRISAT, Bulawayo, Zimbabwe.

Kanyama-Phiri, G.Y. et al. 2000. Towards integrated soil fertility management in Malawi: Incorporating participatory approaches in agricultural research. Working Paper Managing Africa Soils No.11. Russel Press, London, UK

Kerr, R.B., et al. 2007. Participatory research on legume diversification with Malawian smallholder farmers for improved human nutrition and soil fertility. Exp. Agric. 43(4), 437-453.

Mhango, W.G., et al. 2012. Opportunities and constraints to legume diversification for sustainable maize production on smallholder farms in Malawi. Ren. Agric. Food Syst. 28:234-244.

Mhango, W.G. 2011. Nitrogen budgets in legume-based cropping systems in Northern Malawi. PhD Thesis. Michigan State University, USA.

MoAFS. 2012. Guide to Agricultural Production and Natural Resource Management in Malawi. Agricultural Communications Branch, Lilongwe, Malawi.

Mohammadi, K., et al. 2012. Effective factors on biological nitrogen fixation. Afr. J. Agric. Res. 7(12), 1782-1788.

Nanganoa, L.T., et al. 2019. Impact of Different Land-Use Systems on Soil Physicochemical Properties and Macrofauna Abundance in the Humid Tropics of Cameroon. App. Environ. Soil Sci. 1, 5701278.

Ngwira, A.R., et al. 2020. Productivity and profitability of maize-legume cropping systems under conservation agriculture among smallholder farmers in Malawi, Acta Agriculturae Scandinavica, Section B — Soil & Plant Science, DOI: 10.1080/09064710.2020.1712470

Njira, K.O.W., et al. 2017. Biological nitrogen fixation by pigeon pea and cowpea in the double-up and other cropping systems on the Luvisols of Central Malawi. Afr. J. Agric. Res. 12(15), 1341-1352.

Njira, K.O.W., et al. 2012. Biological nitrogen fixation in sole and doubled-up legume cropping systems in the sandy soils of Kasungu, Central Malawi. J. Soil Sci. Manage. 3(9):224-230.

Olufowote, J.O., Barnes-McConnell, P.W. 2002. Cowpea dissemination in West Africa using a collaborative technology transfer model. Bean-Cowpea Collaborative Res Support Program.

Palm, C.A., et al. 1997. Combined use of organic and inorganic nutrient sources for soil fertility maintenance and replenishment. In: Buresh RJ, Sanchez PA and Calhoun F (eds), Replenishing soil fertility in Africa, SSSA Special Publication Number 51., Madison, Wisconsin, USA pp. 151-192.

Phiri, A., et al. 2024. Comparative effects of legume-based intercropping systems involving pigeon pea and cowpea under deep-bed and conventional tillage systems in Malawi. Agrosys, Geosci Environ, 7(2), e20503.

Shafi, M., et al. 2007. Soil C and N dynamics and maize (Zea mays) yield as affected by cropping systems and residue management in Northwestern Pakistan. Soil Tillage Res. 94:520–529

Stagnari, F., et al. 2017. Multiple benefits of legumes for agriculture sustainability: an overview. Chemical and Biological Technologies in Agriculture, 4, 1-13.

World Bank. 1996. Natural Resource Degradation in Sub-Sahara Africa. Restoration of soil fertility. Africa Region. World Bank, Washington D.C. USA.

Zingore, S., et al. 2015. Soil degradation in sub-Saharan Africa and crop production options. Better Crops 99(1):24–26.