By Robert Mikkelsen

Phosphorus is vital for crop productivity in Africa but limited by low soil reserves, strong fixation, and poor recovery. The article emphasizes improving phosphorus use efficiency through 4R Nutrient Stewardship, soil management, and crop breeding innovations. Site-specific strategies and integrated approaches are essential for sustainable yields and food security.

Phosphorus (P) is essential for crop growth and food security, yet it remains one of the most limiting and misunderstood nutrients in African agriculture. The soils of Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) are among the most highly weathered on Earth, characterized by low native P reserves, high P sorption capacity, and chronic nutrient depletion. At the same time, P fertilizer can be costly and is often used sparingly, leading to low yields and inadequate economic returns for millions of farmers. Improving phosphorus use efficiency (PUE) is not just an agronomic challenge, but also an economic and food-security imperative.

The essentiality of phosphorus for plant nutrition and crop yield

Phosphorus is indispensable for nearly every biological process in plants. Its role begins at the molecular level and expands to affect every aspect of plant growth, including crop yield and quality.

The plant demand for P begins early and continues throughout the growing season, with crops such as maize taking up P continuously from emergence to physiological maturity. Deficiency in the early stages may reduce root development, limit canopy formation, and cause irreversible yield losses, even if P is supplied later.

Phosphorus requirements in African cropping systems

The highly weathered nature of most SSA soils means that they are often dominated by iron (Fe) and aluminum (Al) oxides, acidic, and consequentially low in P. This physicochemical nature further increases the transformation of added fertilizer P into less plant-available forms.

Despite this, many crops show strong yield responses to added P, even at relatively low fertilizer application rates. Yet achieving high yields requires continuous replenishment of P removed during harvest, otherwise soils become progressively depleted of nutrients. In addition to mere nutrient replacement, a positive balance (i.e., above removal) is usually required to deliver a multi-year investment in renewed soil P capital.

Why phosphorus fertilizer recovery is low

Even though P is essential for crop nutrition, it is common that only 10 to 20% of applied P fertilizer is recovered by crops in the first growing season. In African soils, recoveries can sometimes be even lower. There are two major reasons for this:

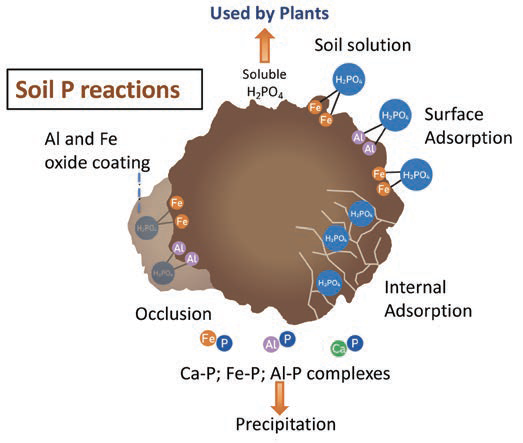

A. Soil reactions that “fix” phosphorus

Once fertilizer applied to soil, phosphate ions react rapidly with Fe, Al, and calcium (Ca) to form less soluble compounds (Fig. 1). These reactions include:

Adsorption: Phosphate attaches to surface of clay minerals and Al/Fe oxides.

Precipitation: Phosphate combines with Ca, Fe, or Al to form minerals with low solubility.

Occlusion: P becomes trapped within mineral structures where roots cannot access it.

The processes responsible for removing P from the soil solution begin within hours or days of fertilizer application. The gradual P conversion to less-soluble chemical compounds can continue for months or years. Although the added P still remains in the soil, its plant availability and solubility is greatly reduced during the season of application as soil minerals tie up P into forms that plants cannot readily use. Many African soils are sometimes referred to as “hungry” soils because they have a large capacity to adsorb added P fertilizer and remove it from the soil solution, and these soils are slow to release the P again.

In many African soils, where Al/Fe oxides dominate, conversion of P to less soluble forms can be extreme. A small dose of broadcast P may become largely unavailable before roots have a chance to access it and it slowly dissolves again over a longer period.

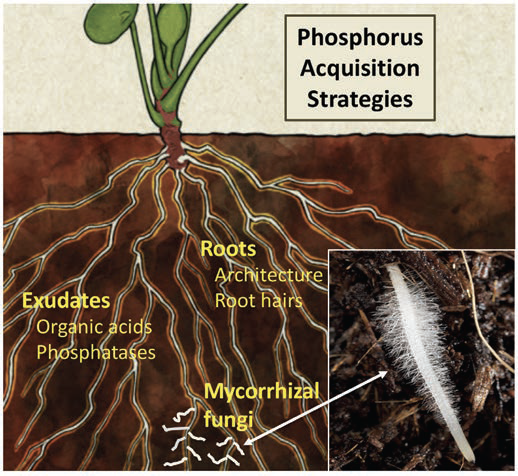

B. Limited root exploration and access

Plants can only take up P that is within a few millimeters of their root surface (Fig. 2). This small area surrounding each root (1 to 3 mm), termed the rhizosphere, is vastly different from the soil further from the root. Within the rhizosphere, plant roots are excreting a variety of soluble sugars, organic acids, and enzymes that facilitate a burst of microbial growth and cause P to be more soluble in the soil solution. However, since P moves slowly and diffuses very short distances, uptake is influenced by:

Greater root density and branching allowing better exploration of the soil and increased interception of diffusion-limited P.

Root hairs extending the reach by another millimeter or more, increasing the root surface area and uptake in the P-depletion zone.

Soil moisture enabling greater P difusion towards the root.

Mycorrhizal fungi and benefcial microbes facilitating P solubilization and uptake.

Root exudates solubilizing organic and inorganic forms of P.

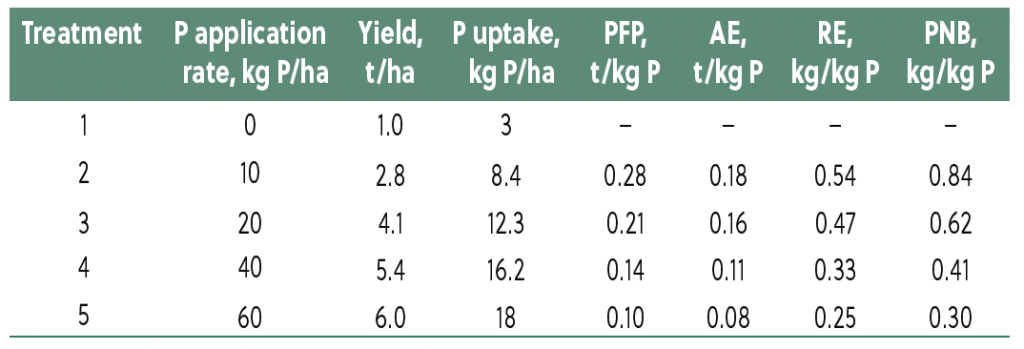

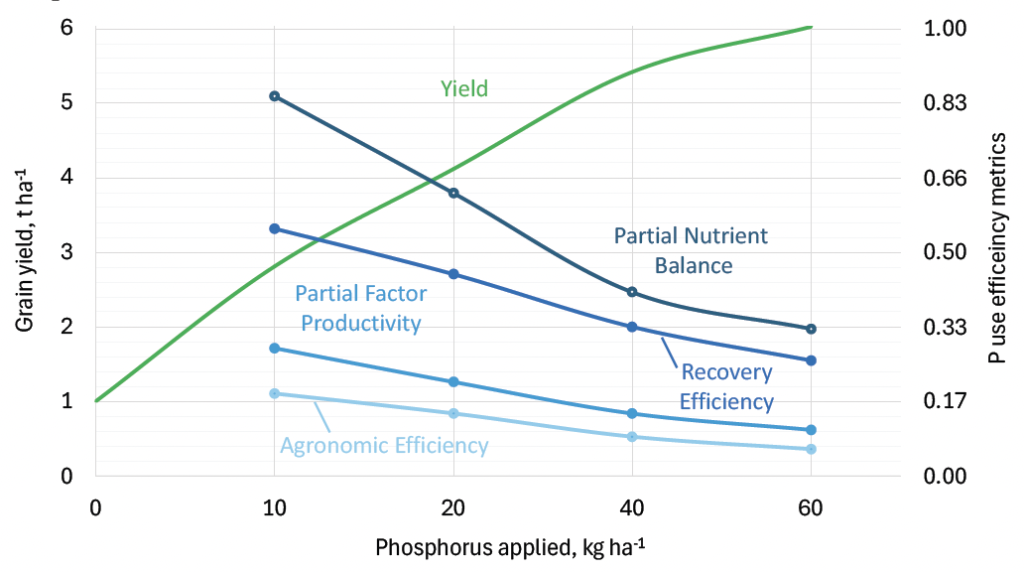

Table 1. Typical response of maize grain to added P fertilizer used to calculate four measures of P efficiency (hypothetical data).

In acidic soils, the presence of soluble Al is damaging to root hairs and can stunt the entire root system, thereby restricting uptake of P. Many African farms suffer from both low soil P concentrations and harmful efects from excessive Al at low pH. This combination of strong P fixation and limited root access contributes to the low seasonal recovery of P fertilizers in many regions.

How phosphorus use efficiency is calculated

There are large differences reported on how much of the P fertilizer is recovered by crops. Some estimates show that as little as 10% of the added P fertilizer is taken up by plants, while other reports show that P recovery can exceed 70–90%. These discrepancies arise from how P recovery is calculated and the time frame considered in the calculation.

Phosphorus use efficiency (PUE) can be expressed in several different ways, and each method answers a different agronomic question. The method of calculating PUE substantially affects the numerical estimate. When referring to PUE, it is necessary to know what it means and how it is calculated.

Here are some of the common ways of calculating “efficiency” (Table 1; Fig. 3).

Partial Factor Productivity (PFP): PFP = Yield / P applied

Measures how productive a field is per unit of fertilizer applied, which is useful for comparing economic efficiency, but not true soil or plant recovery.

Agronomic Efficiency (AE): AE = (Yield with P – Yield without P) / P applied

Shows how much yield increase is obtained per kg of P applied. AE is useful for assessing profitability. Farmers generally want to know what yield benefits they are receiving from applying nutrients and measure their yield gains from fertilizer application. However, this method requires famers to have an unfertilized strip to measure any yield gain resulting from P fertilization.

Recovery Efficiency (RE) RE = (P uptake with fertilizer – P uptake without fertilizer) / P applied

This approach measures actual plant uptake of fertilizer-derived P. This requires knowing both the amount of harvested crop (kg or t), and the P concentration in the crop. The P concentration can be measured by an analytical lab or estimated from published values in the literature. This approach also requires an unfertilized strip for a comparison with fertilized areas.

Partial Nutrient Balance (PNB): PNB = P removed in harvest / P applied

Indicates whether P applications match long-term removal. In many agro-ecosystems, PNB can exceed 70–90% when inputs and harvest outputs are matched, even if short-term P uptake remains low (Syers, et al., 2008). This explains why the diference-method (RE) can appear low, while long-term balances may look much higher. However, in many African soils nutrient balances may not provide a clear short-term picture since a high fraction of fertilizer P can be fxed in biologically unavailable forms.

Taking a multi-year approach considers the strong residual efect of P as the basis for the concept of investing in “soil P capital” to enhance long-term productivity. Repeated applications of inorganic and organic P sources will improve P fertility as a function of time. But the profitability of repeated P additions needs to be considered from an entire farm-system perspective.

Improving phosphorus recovery through soil management and 4R Nutrient Stewardship

Farmers need practical strategies to make advancements in their fertilization practices. The 4R Nutrient Stewardship framework provides a combination of agronomic, chemical, and biological approaches for improving P use efciency.

1. Right Source

- Use soluble mineral P fertilizers where rapid crop response is needed.

- Combine mineral P with locally available organic materials (manure, compost, residues) which:

- provide an additional input of external P,

- supply organic acids that compete with P adsorption reactions,

- improve soil structure and moisture-holding capacity,

- stimulate microbial P cycling,

- help alleviate Al toxicity to roots.

- Rock phosphate may be appropriate, especially on acidic soils and in long-term cropping systems.

2. Right Rate

- Select P fertilizer applications on local or regional soil tests where available, yield targets, and local calibration data.

- Avoid under-application, which leads to:

- low yields and biomass,

- limited root growth,

- poor economic returns per unit of grain produced.

- Avoid large over-applications, which increase fIxation and may also reduce economic returns.

3. Right Time

- Synchronize applications with crop demand.

- Sidedress or place P at planting rather than broadcasting widely.

- Avoid applying early in long dry periods when diffusion is minimal.

4. Right Place

- Placement is often the most powerful tool for managing P in many African soils.

- Banded fertilizer concentrates P near the root zone, reducing soil contact and slowing P adsorption.

- Spot application (microdosing) near the seed is especially efective for smallholder farmers using low P application rates.

- Broadcast-and-incorporate techniques will improve the overall P concentration in soil but may not result in an immediate P response to the following crop.

Liming acidic soils is another critical strategy. Raising the soil pH reduces Al and Fe reactivity, thus improving P availability and encouraging healthier roots.

Moisture management through mulching, residue retention, and reduced tillage can also enhance P diffusion and P-solubilizing biological activity, improving plant access to soil P.

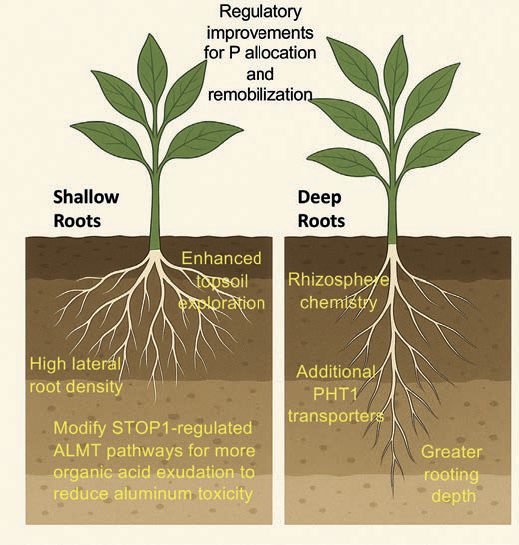

Future opportunities: modifying crops to improve phosphorus acquisition

While soil management is the first step for improving P efficiency, crop genetics may soon offer opportunities to improve P uptake by crops. Current research is exploring root traits that help plants better explore soil, solubilize soil P, and use internal plant P more efficiently. Below are a few examples of promising innovations (Fig. 4).

A. Root system architecture modifcations

Modifying these traits could help crops better access fertilizer P, which is typically concentrated in the upper soil profle.

Plant breeding for:

- denser root systems

- shallow root angles for better foraging of the P-rich topsoil

- greater root hair length and density

- more lateral branching for greater soil exploration

B. Rhizosphere chemistry and exudation

Plants naturally release a variety of organic acids and P-solubilizing enzymes (such as phosphatase) that improve P solubility. Modifying the rootzone to enhance these abilities may lead to:

- improved solubilization of Al- and Fe-bound P

- greater P release from organic P pools

- increased stimulation of P-solubilizing microbes.

C. Improved P transporters and internal efficiency

Biotechnology tools (e.g., CRISPR/Cas editing) may allow modification of:

- PHT1 phosphate transporters for increased uptake at low soil P concentrations,

- genes controlling exudation pathways (STOP1, ALMT family) to protect roots from Al toxicity,

- regulatory systems that improve P use efficiency inside the plant.

Summary

Phosphorus is foundational to crop productivity and food security. Its management is especially critical for African agriculture. Low native soil P, strong fixation, and limited fertilizer use all combine to suppress yields and reduce profitability. Yet with improved soil management, targeted fertilizer inputs, and adoption of the 4R Nutrient Stewardship principles, P use efficiency can be significantly improved.

Getting the greatest agronomic and economic return from P fertilizer is most likely to occur when practices are customized for local soils and conditions. The wide diversity of soil, cropping, and economic capital makes broad generalizations unlikely to succeed, where site-specific management of P is needed. Advice from local experts is necessary for success.

The challenge ahead involves not only managing soil and fertilizer P more wisely but also breeding crop varieties capable of thriving in Africa’s unique soil conditions. When agronomy, soil science, and plant genetics work together, farmers can achieve higher yields, reduced environmental risks, and a more resilient food system.

Dr. Mikkelsen (rob.mikkelsen@gmail.com) is Adjunct Professor, North Carolina State University, Raleigh, North Carolina, USA.

Cite this article

Mikkelsen, R. 2025. Managing Phosphorus for Profitable and Sustainable Crop Production in Africa. Growing Africa 4(2):9-13. https://doi.org/10.55693/ga42.CLST4833

REFERENCES

Syers, J.K. et al., 2008. Efficiency of soil and fertilizer phosphorus use. https://www.fao.org/4/a1595e/a1595e00.htm