By Damiano Kwaslema, Tindwa Hamisi, Deodatus Kiriba, James Mutegi, Esther Mugi-Ngenga, and Nyambilila Amuri

The study evaluates zinc fertilization strategies to improve rice yield in Tanzania’s Kilombero district. Field trials compared Zn sources, rates, and application methods under rain-fed and irrigated conditions. Soil-applied ZnSO. and foliar ZnSO. within a NPKS fertilizer blend were most optimal in terms of yield and in addressing the issues of widespread Zn deficiency and food security. A participatory approach enabled researchers and farmers to work together and collect data and observe rice performance under different zinc and microbial fertilizer rates and regimes in Kisawasawa village, Kilombero District, Tanzania.

Rice is one of the most important staple crops in Tanzania, a significant contributor to both food security and livelihood, with about equal amounts of its production destined either for household use or to be marketed for income (TZA-NBS-AASS, 2023). However, achieving optimal rice yields and nutritional quality is a challenge due to prevailing soil nutrient deficiencies. Low productivity measured against an increasing demand are also the main drivers for encroachment of rice farming into protected areas in the Kilombero valley of Tanzania.

The most widely studied and deficient nutrients for rice production are nitrogen (N) and phosphorus (P), which represent two of the three primary nutrients found in most fertilizers. Limited emphasis on supplementation of other required nutrients has resulted to low use efficiency for applied fertilizers and depletion of micronutrients in most soils (Senthilkumar et al., 2021).

Zinc (Zn) deficiency in soils is a widespread problem affecting rice production in the Kilombero valley. Introduction of Zn in fertilizer blends is one of the efforts used to correct this deficiency. However, farmers’ have limited access to Zn-enriched fertilizers and knowledge on their proper application. Most of the available fertilizer formulation contain 0.007-4.6% Zn (AGRA.IFDC-AFAP, 2018), supplying 0.03-9.5 kg Zn/ha based on recommendation of 100 kg N/kg and 40 kg P/ha, and fertilizer grade. It is uncertain as to which fertilizer formulation will supply optimum Zn for a particular location based on soil fertility status, to guide their distribution. Furthermore, studies have highlighted the need for identifying the optimal source, application rate, method, and frequency of Zn application to maximize its effectiveness in improving rice yields (Khampuang et al., 2021). Different Zn sources, such as zinc sulfate (ZnSO4) and zinc oxide (ZnO), and application methods such as soil or foliar application or root dipping vary in their bioavailability. This can influence Zn uptake and subsequent rice growth, yield and potential to fight hidden hunger. Therefore, addressing Zn deficiency through optimized fertilization strategies is essential for enhancing both the rice yield and yield quality.

The study outlined below sought optimal Zn fertilization strategies for rice grown under irrigated and rain-fed conditions in the Kilombero district. By evaluating different Zn sources, application rates, methods, and frequencies, this research aims to identify practices that can enhance rice production, thereby contributing to improved food security and economic outcomes of farmers. Evidence-based recommendations will allow farmers to optimize Zn use in rice production, ultimately improving yield outcomes and supporting sustainable agricultural development.

Study area description

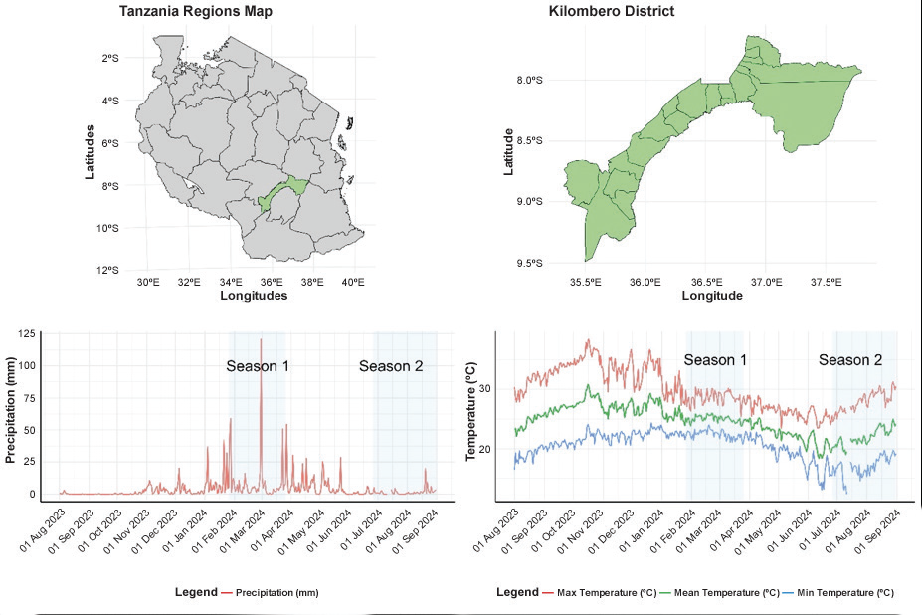

The field experiments were conducted in the Kisawasawa rain-fed scheme, and the Mkula irrigation scheme (Fig. 1). These two represent some of the most prominent rice growing areas in Kilombero district, making it one of the three districts contributing to Morogoro’s leading contribution to rice production in Tanzania, with 22% of land under rice production and 17% of rice production in Tanzania (TZA-NBS-AASS, 2023). The Kilombero district falls within a tropical savanna climate. The area has two distinct rainy seasons: a short season from October to December and a longer season from March to May, interspersed with dry spells, with the mean annual rainfall of between 1200-1400 mm. The average temperature ranges from 22-23°C.

Climate condition during study period

Significant climate variability was observed during the two experimental seasons in Kilombero (Fig. 1). In season 1 (January 2024-March 2024), temperatures and rainfall were generally favorable for rice growth, with mean temperatures around 25°C. Both the frequency and intensity of rainfall were high, reaching up to 125 mm/day. In contrast, season 2 (June 2024-September 2024) experienced relatively lower temperatures and rainfall during early stages of crop growth, with average minima of less than 15°C, and average maxima of < 35°C.

Farmer field experimental layout

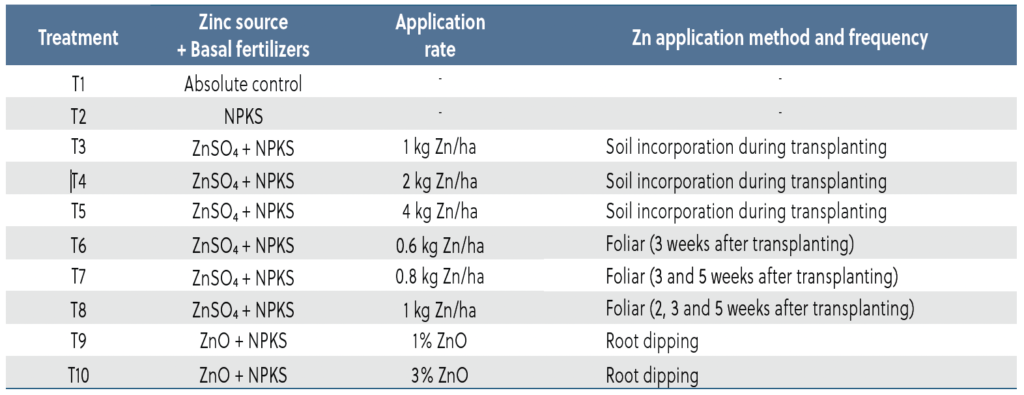

The field experiments were conducted in the farmers’ fields where treatments (Table 1) were set up by researchers. Participating farmer groups jointly managed the fields and collected data with researchers to facilitate co-learning. Prior to rice planting, soil samples were collected to analyze specific physicochemical properties. Soil samples were collected at 0-20 cm depth and analyzed using standard wet chemistry procedures at the Soil Science Laboratory of the Sokoine University of Agriculture. The rice variety TXD 306 (SARO 5) was used as a test crop. The experiments were laid out in a randomized complete block design with ten treatments and three replications. The fertilizers used were urea (46-0-0), Minjingu NPKS fertilizer and Zn as ZnSO4·H2O and ZnO. The top dress N fertilizer was applied four weeks after planting.

Table 1. Description of experimental treatments.

Measurement of plant growth parameters and yield components

As a proxy of evaluating effectiveness of Zn fertilization strategies, we measured plant height, tiller number, grain yields, yield components, and biomass for each plot at maturity as described in Gomez, (2006). Tiller number was counted per plant in single-plant hills, with productive and unproductive tillers separated at harvest. Grain yield was calculated by harvesting grains from selected hills, excluding plots with more than 20% hill reduction due to damage and adjusted to 14% moisture content. The 100-grain weight was measured by counting and weighing 1,000 fully developed grains. Yield components such as panicle number, number of filled grains per panicle, and grain weight were also assessed using standardized sampling and measurement procedures. Low and high farm gate prices were collected for seasons 2022/2023 and 2023/2024 through farmer interviews to calculate gross revenue from rice to determine the financial implications of each treatment. Averaged over both seasons prices ranged between Tsh 800-1,166.67 per kg at Kisawasawa and Tsh 1,066-1,233 per kg at Mkula.

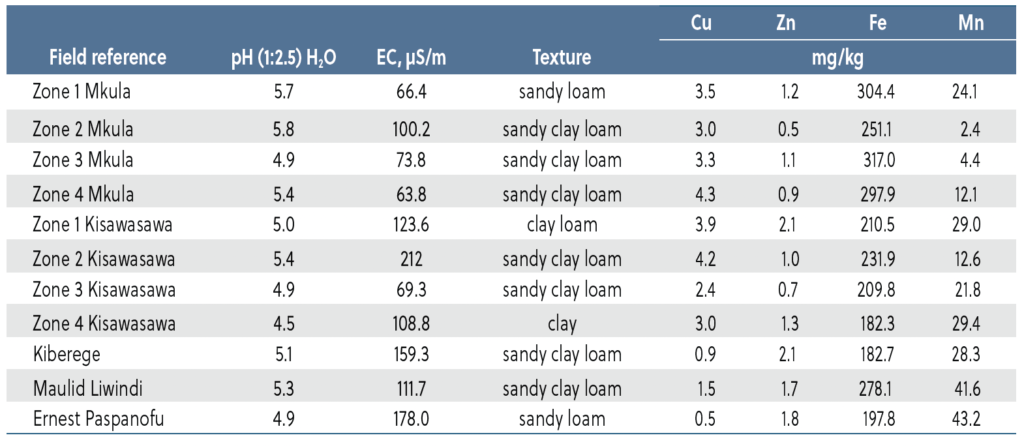

Status of rice growing farms of Mkula and Kisawasawa irrigation schemes

Soil laboratory analysis (Table 2) indicate pH ranged from 4.9-5.8 at Mkula, categorizing the soils as moderately acidic. The texture varied from sandy loam in Zone 1 to sandy clay loam in Zones 2, 3 and 4. Zinc concentrations in Mkula ranged from 0.5-1.2 mg/kg, with Zone 2 showing a critically low Zn concentration of 0.5 mg/kg, below the critical threshold of 0.6 mg/kg for rice (Fairhurst et al., 2007). Although Zones 1, 3 and 4 had slightly higher Zn concentrations (1.2, 1.1 and 0.9 mg/kg, respectively), they remained in the marginal range, indicating that Zn supplementation is necessary to address potential Zn deficiency across the entire Mkula site. Copper (Cu) concentrations ranged from 3.0-4.3 mg/kg, well above the critical level of 0.1-0.3 mg/kg, indicating sufficient Cu availability. Iron (Fe) concentrations were high across all zones, ranging from 251-317 mg/kg, far exceeding the critical level of 2-5 mg/kg. Manganese (Mn) concentrations varied significantly, with Zone 2 showing a critical deficiency of 2.4 mg/kg, below the threshold of 12-20 mg/kg. In contrast, Zones 1, 3 and 4 had Mn concentrations of 24.1, 4.4 and 12.1 mg/kg, respectively, indicating that while Zone 2 requires Mn supplementation, other zones have sufficient Mn for rice growth.

Table 2. Soil analysis results on micronutrient status of rice growing farms of Mkula and Kisawasawa irrigation schemes, Kilombero, Tanzania.

In Kisawasawa, the pH ranged from 4.5-5.4, indicating acidic conditions. The soil textures were predominantly clay and sandy clay loam. Zinc concentrations ranged from 0.7-2.1 mg/kg, with most zones having Zn concentrations above the critical deficiency threshold, though Zone 3 exhibited marginal Zn status at 0.7 mg/kg. Copper concentrations in Kisawasawa were consistently above the critical deficiency level, ranging from 2.4-4.2 mg/ kg. Iron concentrations were similarly high, ranging from 182-231 mg/kg, and Mn concentrations were sufficient across the site, with values ranging from 12.6-43.2 mg/kg.

This analysis suggests that Zn deficiency is a key concern in both Mkula and Kisawasawa irrigation schemes, with specific zones in each village exhibiting marginal to deficient Zn concentrations, given that most farmers rely solely on macronutrient supplementation (Senthilkumar et al., 2021). Zinc supplementation, through either soil or foliar application, is recommended to improve rice productivity, particularly in Zn-deficient areas such as Mkula’s Zone 2 and Kisawasawa’s Zone 3.

Effect of zinc fertilization strategies on rice growth

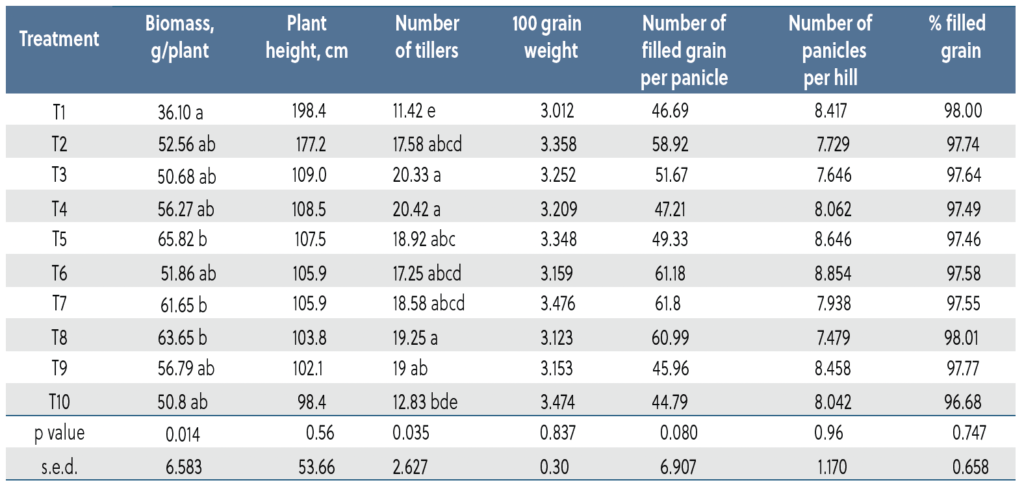

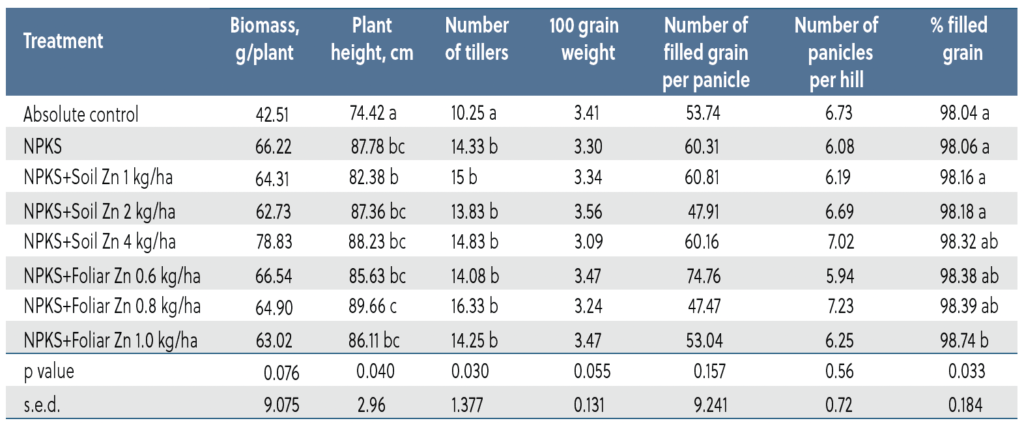

The results revealed significant differences among treatments at both Kisawasawa (Table 3) and Mkula (Table 4). Significant differences due to treatments were observed for biomass accumulation (p= 0.014) at Kisawasawa, but not Mkula (p=0.076). The number of tillers showed significant differences due to treatments in both Kisawasawa (p=0.035) and Mkula (p=0.030). In all treatments and in both sites, the zero fertilizer treatment had the lowest of all growth parameters measured, while the fertilized treatments did not differ in growth parameters measured. Therefore, fertilizers applied improved growth of rice, but there were no significant differences between fertilizer types.

Table 3. Effect of varying sources, rates and application methods of zinc on rice growth and yield parameters at Kisawasawa, Kilombero, Tanzania.

Table 4. Efect of varying sources, rates and application methods of zinc on rice growth and yield parameters at Mkula, Kilombero, Tanzania.

The percentage of filled grain did not show significant differences at the Kisawasawa site (p = 0.747) but was significant at Mkula (p=0.033) (Table 3 and 4). The highest percentage (98.74%) such as T6 and T7, also had high percentages of was recorded in treatment T8 (1 kg Zn/ha, foliar), filled grain, further highlighting the effectiveness of while the control (T1) and T2 (NPKS only) had foliar Zn application. The effect of Zn fertilization slightly lower percentages (98.04% and 98.06%, strategies on 100-grain weight showed no significant respectively). Treatments with foliar-applied ZnSO4, differences in both sites.

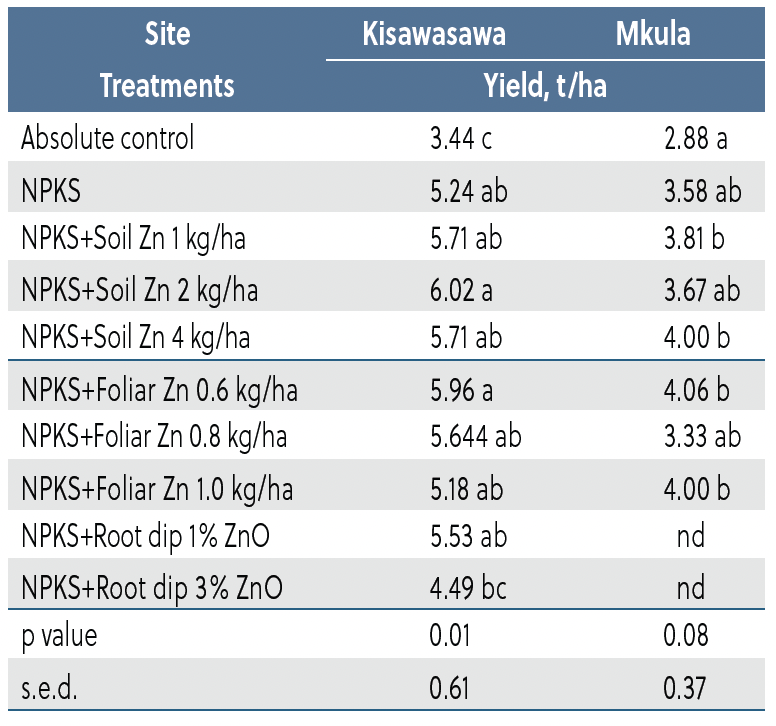

Effect of zinc fertilization strategies on rice grain yield

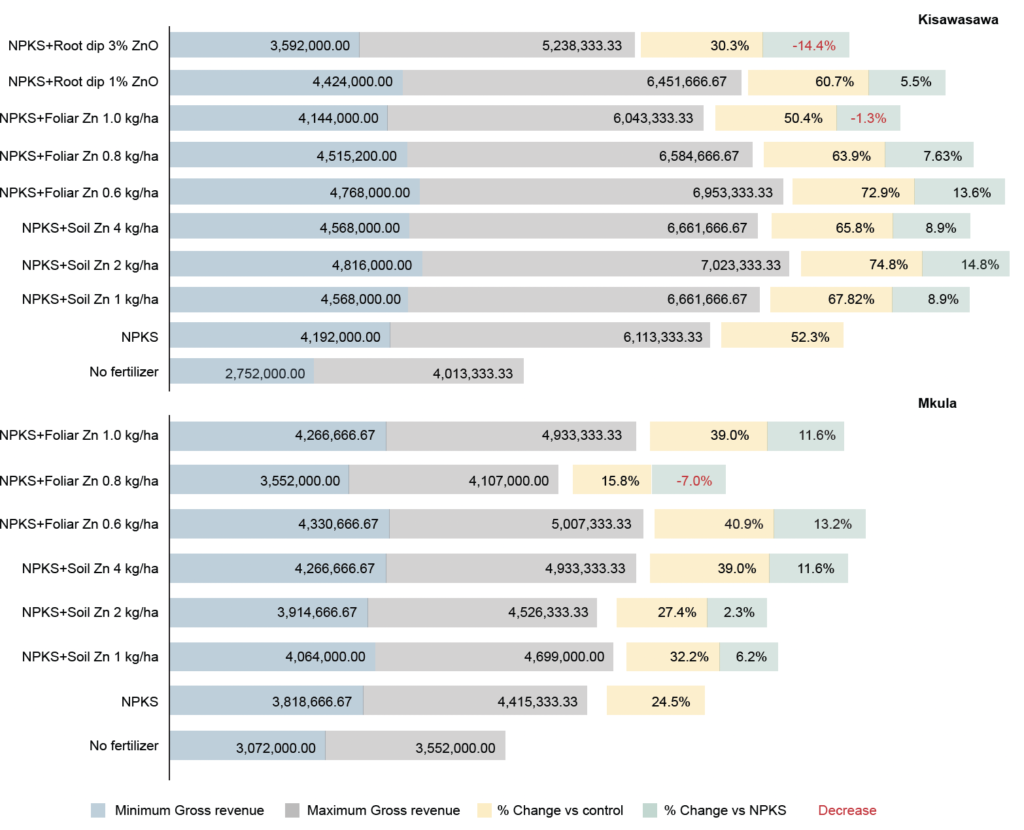

Zinc fertilization strategies significantly affected grain yield at both experimental sites (Table 5). Application of all fertilizers significantly increased yield and gross income by 2-75% over the no fertilizer treatments, while addition of soil and foliar Zn at all rates increased grain yield and gross income by 15% relative to the NPKS (Fig. 2). Exceptions included the slight decrease in yield in T8 and T10 at Kisawasawa and T7 at Mkula.

Table 5. Yield response of rice treated with varying zinc fertilization strategies in Mkula and Kisawasawa irrigation schemes, Kilombero, Tanzania.

The Kisawasawa site had consistently higher yields across all treatments, with the highest yield of 6.02 t/ha obtained in T4 (soil applied NPKS and soil incorporation of NPKS plus ZnSO4 prior transplanting at 2 kg Zn/ha). The highest yields in Mkula were obtained in T6 (NPKS + foliar applied ZnSO4 at rates of 0.6 kg Zn/ha) (4.06 t/ha), T5 (NPKS + soil applied 4 kg Zn/ha) and T8 (NPKS seedlings dipping in 1% ZnO), both of which recorded 4 t/ha. These results show site-specific responses of rice to Zn fertilization. Furthermore, root dipping rice seedlings in 3% suspensions of ZnO decreased rice yield in Kisawasawa.

Conclusions

Fertilizer combination that supplies soil applied N, P, K, and S with soil applied ZnSO4 at the rate of 2 kg Zn/ha is a suitable strategy for rain-fed area with acid soil deficient in those nutrients. On the other hand, foliar applied Zn at the rate of 0.6 kg Zn/ha in addition to N, P, K, and S is a suitable strategy in the irrigated rice-growing areas. Use of a high rate of ZnO fertilization strategies at 3% through seedling root dipping did not suit rice production in Kilombero and may need further research for optimization. Therefore, both soil and foliar applied Zn in the form of ZnSO4 are the best fertilization strategy for rice production in Kilombero district.

Acknowledgement

This research was made possible with funding from APNI under the African Plant Nutrition Research Fund (APNRF).

Mr. Kwaslema and Mr. Hamisi are with the Department of Soil and Geological Sciences, Sokoine University of Agriculture, Morogoro, Tanzania. Mr. Kiriba is with the Tanzania Agricultural Research Institute (TARI), Dodoma, Tanzania. Dr. Mutegi and Dr. Mugi-Ngenga are with the African Plant Nutrition Institute (APNI), Nairobi, Kenya. Dr. Amuri (namuri@sua.ac.tz) is with the Department of Soil and Geological Sciences, Sokoine University of Agriculture, Morogoro, Tanzania.

Cite this article

Kwaslema, D., Hamisi, T., Kiriba, D., Mutegi, J., Mugi-Ngenga, E., Amuri, N.A. 2025. Zinc Fertilization Strategies for Enhanced Rice Production in Kilombero, Tanzania. Growing Africa 4(2):28-34.

https://doi.org/10.55693/ga42.ZYMK9790

REFERENCES

AGRA-IFDC-AFAP. 2018. Assessment of Fertilizer Distribution Systems and Opportunities for Developing Fertilizer Blends in Tanzania. https://agra.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/ Tanzania-Report_Assessment-of-Fertilizer-Distribution.Systems-and-Opportunities-for-Developing-Fertilizer.Blends.pdf

Fairhurst, T., et al. 2007. Rice: a practical guide to nutrient management. International Rice Research Institute, International Plant Nutrition Institute, and International Potash Institute. http://books.irri.org/97898179494_content. pdf.

Khampuang, K., et al. 2021. Nitrogen fertilizer increases grain zinc along with yield in high yield rice varieties initially low in grain zinc concentration. Plant Soil 467, 239–252.

Senthilkumar, K., et al. 2021. Rice yield and economic response to micronutrient application in Tanzania. Field Crops Res., 270.

Sparks, A. 2024. NASA POWER Data from R. https://CRAN.R.project.org/package=nasapower

TZA-NBS-AASS. 2023. Tanzania National Bureau of Statistics Annual Agriculture Sample Survey 2022/23, Version 1.1 of the public use dataset (June 2024), available at the National Data Archive: https://www.nbs.go.tz/tnada/index.php/home