By Thomas S. Jayne, Shamie Zingore, Amadou Ibra Niang, Cheryl Palm, and Pedro Sanchez

Key findings are summarized from a study detailing how international donors and research organizations can more effectively strengthen the capacities of African national agricultural research and extension systems (NARES). International efforts are 0more successful in building the capacities of individuals than in strengthening the NARES institutions. Successful implementation of the Africa Fertilizer and Soil Health Summit and similar initiatives will require stronger national, regional and continental agricultural research systems that can lead and drive these initiatives. The authors identify actions required to strengthen these African systems and effectively implement African-led agricultural initiatives.

Sustainable soil health and fertilizer use in Africa – as well as many other important goals of Africa’s governments and people – depend on building dedicated local scientific expertise to support its agricultural sectors. The challenge is essentially how to build the research, development, and extension (R&D&E) capacity to generate a continuous stream of productivity- and resilience-enhancing technical innovation that can be scaled-out to millions of farm households facing highly varied agro-ecologies and resource constraints.

National capacity boils down to the skills of its people and the performance of its institutions. While there are many national institutions responsible for generating sustainable farm technical innovation, the national agricultural research and extension systems (NARES) are the centerpiece. Without strong NARES, African countries cannot provide technical guidance to their farmers and therefore become dependent on international agricultural research systems (IARS) for achieving national goals related to fertilizer and soil health sustainability. IARS are crucial allies for supporting African agriculture, but they are generally not well-suited to scale-out technical innovations on their own, nor do they have the resources to do so, hence strong NARES on the ground are required to adapt technologies and policies in collaboration with millions of African farmers. Countries that were once relatively poor, but which were able to build strong NARES (e.g., Brazil and many Asian countries), generally achieved impressive agricultural productivity growth, broader agri-food systems development, and rapid increases in living standards (Fuglie et al., 2020; Goyal and Nash, 2016; Pardey et al., 2016).

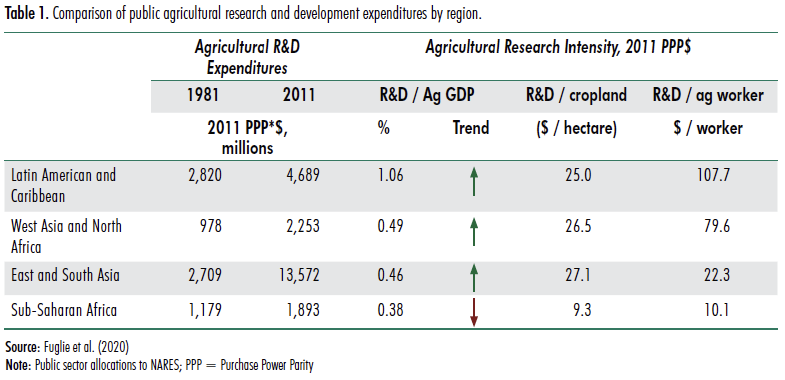

Table 1 presents the levels and trends in agricultural R&D expenditures over time for sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) and other developing regions. Trends are reported for R&D expenditures in relation to agricultural gross domestic product (GDP), hectares of cropland, and the number of agricultural laborers in the country. For all the metrics, funding for agricultural R&D in SSA has been lower than in other regions for many decades. This is consistent with Goyal and Nash (2019), Fuglie et al. (2020), and Stads et al. (2021).

The slow rate of crop yield growth in Africa over the past four decades attests to the need to better understand the actions that African governments and development partners can take to enable their NARES to perform better and contribute to the achievement of resilient, inclusive, and productive agri-food systems. This article takes the premise that strong NARES are at the heart of Africa’s efforts to achieve sustainable agricultural systems, which include soil health and much greater and more efficient use of fertilizers.

This article also addresses how African countries can build the capacity of their NARES to achieve these goals, summarizing key findings and conclusions from a forthcoming study on African NARES (Jayne et al., 2023). The objectives of the report were to pinpoint the reasons for the slow development of African NARES and highlight actions that African governments can take to build the capacity and performance of their NARES.

What exactly are NARES and what do they do that leads to improved soil health and agricultural productivity?

NARES are the system of national institutions that generate and adapt farm technical innovation to be taken up by millions of African farmers. They include the national agricultural research institutions that undertake crop and animal science research, and the national extension systems that work with farmers to adapt and adopt new technologies and practices that lead to improved yields, resilience, and sustainable agricultural intensification. They also include national agricultural universities that ideally create a steady stream of trained professionals to take up positions in the NARES and in the private sector to achieve bi-directional learning between farmers and scientists in support of more resilient, sustainable, and inclusive agricultural performance. NARES include the national policy analysis institutes that guide African governments in identifying broader systemic change necessary to promote sustainable, inclusive, and resilient agricultural growth. Currently, few African NARES conform to this idealized definition. The challenge is how to enhance the effectiveness of NARES.

Main Findings

Four main findings can be highlighted from the study.

First, building strong NARES will require a regional approach at first for many countries. Today, only a few African countries have viable NARES; at least 25 African countries have historically devoted a small fraction of their limited public expenditure to agriculture and their NARES. As a result, they lack a viable national agricultural R&D program or university system required to develop the in-country professionals needed for effective operation of a NARES. Hence delivering soil heath and fertilizer sustainability to farmers in many African countries will require starting with a regional approach. Stads et al. (2021) propose organizing agricultural R&D investment by agro-ecological zones rather than political boundaries, at least for relatively small African countries. Integration of agricultural R&D at the subregional and regional level, through joint research programs and regional centers of excellence, may be the most effective way to allow countries with lagging agricultural research systems to benefit from the gains made in countries with similar agro-ecological conditions that have more advanced systems. Better coordination and a clear articulation of mandates and responsibilities among national, subregional, regional, and global R&D players are essential to ensuring that scarce financial, human, and infrastructure resources are optimized, duplications minimized, and synergies and complementarities enhanced. This is not just a policy consideration for African governments but for continental and regional African development organizations as well.

Better coordination and a clear articulation of mandates and responsibilities among national, subregional, regional, and global R&D players are essential to ensuring that scarce financial, human, and infrastructure resources are optimized, duplications minimized, and synergies and complementarities enhanced.

Second, sustained commitment and funding from African governments is a precondition for building strong NARES and regional and continental agricultural R&D&E systems. Through their Maputo Declaration commitments,

African leaders recognize that agriculture is a critical engine for economic development, job creation, and poverty reduction. Yet by most metrics, SSA governments spend very little on agricultural R&D (Stads et al., 2021). African leaders must become convinced that greater commitment to their NARES organizations will help them achieve many of their most valued national policy objectives. Sustained political commitment could be galvanized by respected champions of African agriculture who compellingly demonstrate to political leaders how the performance of their NARES affects, in various direct and indirect ways, many of their most cherished policy goals. Leaders would then need to be guided regarding what greater commitment means in practice: sustained funding at greater levels, serious performance monitoring, and accountability. The national and international research community may also do more to demonstrate to African leaders how and why most of their national policy goals, including sustainable soil heath and fertilizer use, depend on improving the capabilities of African tertiary education systems to generate a continuous stream of well-trained agricultural scientists needed to sustainably operate African NARES. Effective NARES require skilled people.

Third, international donors and research organizations can and must do more to build the capacity of African NARES and regional R&D organizations. A serious stocktaking by international partners, including donors, the CGIAR, and international universities, is warranted to develop a greater appreciation of how their own effectiveness (i.e., impact generated per dollar of donor funds allocated to international research systems) depends on the performance of NARES, and that, by extension, efforts to build the capacities of these partners should be prioritized more seriously. The fact that much improved genetic materials developed by international research fail to be commercially distributed and adopted by farmers demonstrates how impact of the CGIAR and other international partners is constrained by severe weaknesses and challenges faced by NARES. System performance is constrained by its weakest link in the system. Support for building strong NARES needs to be pursued with much greater commitment by international donor organizations; impacts from their own grants and projects in fact depends upon it.

Donor commitment to supporting African agriculture requires direct engagement with the NARES. After the African governments, international and African funding organizations hold the key to strengthening African R&D&E systems by the grants that they make. We encourage donors to consider ensuring that grants related to African agricultural technical innovation require including organizations in the NARES at the design stage, supporting nationally led priority setting agendas, and ensuring that NARES interests and priorities are reflected in proposal and budget development. Grants with co-directors from NARES organizations would enable these organizations to feel greater ownership and commitment to achieving the objectives of the grant. Donor and development bank funding should be consistent with priorities set by national stakeholder processes, which can draw upon the expertise of international, African continental, and regional partners.

In many cases, these proposals for consideration may entail (a) putting host-country institutions in the lead, supported by international expertise; (b) the priority agenda being defined by national governments to build local ownership; and (c) taking a systems approach to NARES development, which requires socio-economic/policy analysis units to be integrated into the NARES.

Fourth, confront the issue of “work-arounds”: Some donor organizations are reluctant to directly partner with public sector entities and often create parallel structures to the NARES that carry out activities that duplicate the mandates of the NARES. While donors may ensure greater accountability for their funding by creating their own partners working on the ground, the long-term impacts are unclear, as they may weaken or marginalize organizations in the NARES that African governments rely upon to carry out the public goods role of agricultural R&D&E in their countries. Resentment, lack of cooperation, missed opportunities, and limited long-term impact are common outcomes when donors create and fund new organizations to carry out tasks that overlap with the mandate of existing national entities. n

Summary: Who needs to do what?

Actions by African governments

The most crucial step to improving the performance of NARES is for national governments to increase their funding and commitment to supporting their own NARES, to monitoring performance, and to demand greater accountability for results.

• Increase overall public disbursements to agriculture and raise the share of public agricultural expenditures going to organizations in the NARES. Rather than relying too much on donor contributions and development bank loans to fund critical areas of research, governments need to determine their own long-term national priorities and design relevant, focused, and coherent agricultural R&D&E programs accordingly.

• Incentivize the private sector to collaborate more with African NARES. Governments’ calls for the private sector to step up and support African farmers often fall on deaf ears unless governments provide the necessary incentives. Many private agribusiness firms are already heavily involved in supporting farm technical innovation in Africa, including soil health and fertilizer use. But African governments could leverage much greater support from the private sector by making it attractive for the private sector to invest in, and collaborate with, African NARES, by providing a favorable policy and enabling environment, effective accountability frameworks, and by stepping up to support their own NARES.

• Ensure that budget lines to organizations in the NARES are fully disbursed each year. Stads et al. (2021) found that in many cases, governments did not fully disburse approved budgets to their NARES.

Actions by African university leadership

• Prioritize improving post-graduate training in faculties of agriculture, including sandwich programs at qualified universities. The University of Pretoria Collaborative Masters in Agricultural Economics and Extension provides a useful model for consideration. This program allowed MSc students to take courses both at their home university and at the University of Pretoria for a year, where international faculty and UP faculty taught and mentored them, guided their thesis work, and supported their efforts to be placed in suitable organizations on the African continent after graduation. External reviews considered the program highly effective in raising the supply of well-trained MSc agricultural economists and could be considered to build African capacity in other agricultural disciplines.

• The senior management of many African universities tend to regard their resources and budget limits as being exogenously determined by budget allocations from their central governments. But African universities could potentially expand their budgets by proactively competing for international donor resources. They could form partnerships with CGIAR organizations, international universities, and/or relevant organizations in the global south to prepare proposals for funding new activities or expanding the funding for existing activities.

Actions by international donors and research systems

• Encourage donor grants targeted to CGIAR or international universities to include organizations in the NARES at the design stage, ensuring that NARES interests and priorities are reflected in proposal and budget development. Donors could do more to ensure that their grants are co-led by organizations in the CGIAR and the NARES, starting from project design, so that NARES or regional R&D&E systems are brought in from the beginning.

• Explore opportunities to leverage the formidable R&D&E systems of the private sector. The private sector is currently the least developed source of sustainable financing for agricultural R&D&E in Africa.

• Donor and development bank grants in support of sustainable fertilizer use and soil health should be consistent with priorities set by national governments.

• Donors that can afford to take a long-term time horizon for impact, should see the necessity of long-term support to the NARES, extension, and agricultural universities with long-term commitments, moving away from grants that focus on low-hanging fruit with short-term impact.

Dr. Jayne (e-mail: jayne@msu.edu) is University Foundation Professor Emeritus, Michigan State University, East Lansing, USA. Dr. Zingore is APNI Director of Research & Development, Benguérir, Morocco. Dr. Ibra Niang is CEO, Afrik Innovations, Dakar, Senegal. Dr. Palm is Professor, University of Florida, Gainesville, USA. Dr. Sanchez is Professor Emeritus, University of Florida, Gainesville.

Cite this article

Jayne, T.S., Zingore, S.Z., Ibra Niang, A. Palm, C., Sanchez, P. 2023. Building Research, Development, and Extension Capacity for Sustainable Fertilizer Use and Soil Health in Africa, Growing Africa 2(1), 10-14. https://doi.org/10.55693/ga21.BELW4471

REFERENCES

Fuglie, K., et al. 2020. Harvesting Prosperity: Technology and Productivity Growth in Agriculture, Washington, D.C., World Bank.

Goyal, A., Nash, J. 2016. Reaping Richer Returns, Preliminary Overview: Public spending priorities for African agriculture productivity growth. Washington, DC: World Bank. © World Bank. https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/25782

Jayne, T.S., et al. 2023. (forthcoming). Building 21st Century National Agricultural Research and Extension Systems in Africa. Report. The Breakthrough Institute, San Francisco.

Pardey, P., et al. 2016. Returns to food and agricultural R&D investments in Sub-Saharan Africa, 1975–2014. Food Policy, 65 (Dec.), 1-8.

Stads, G.-J., Nin-Pratt, A., Beintema, N. 2021. Boosting Investment in Agriculture research in Africa: Building a case for increased investment in agricultural research in Africa. Report prepared for the African Union Fourth Ordinary Session of the Specialized Technical Committee on Agriculture, Rural Development, Water, and Environment to be held during 13–15 Dec. 2021. Africa Science and Technology Indicators (ASTI).